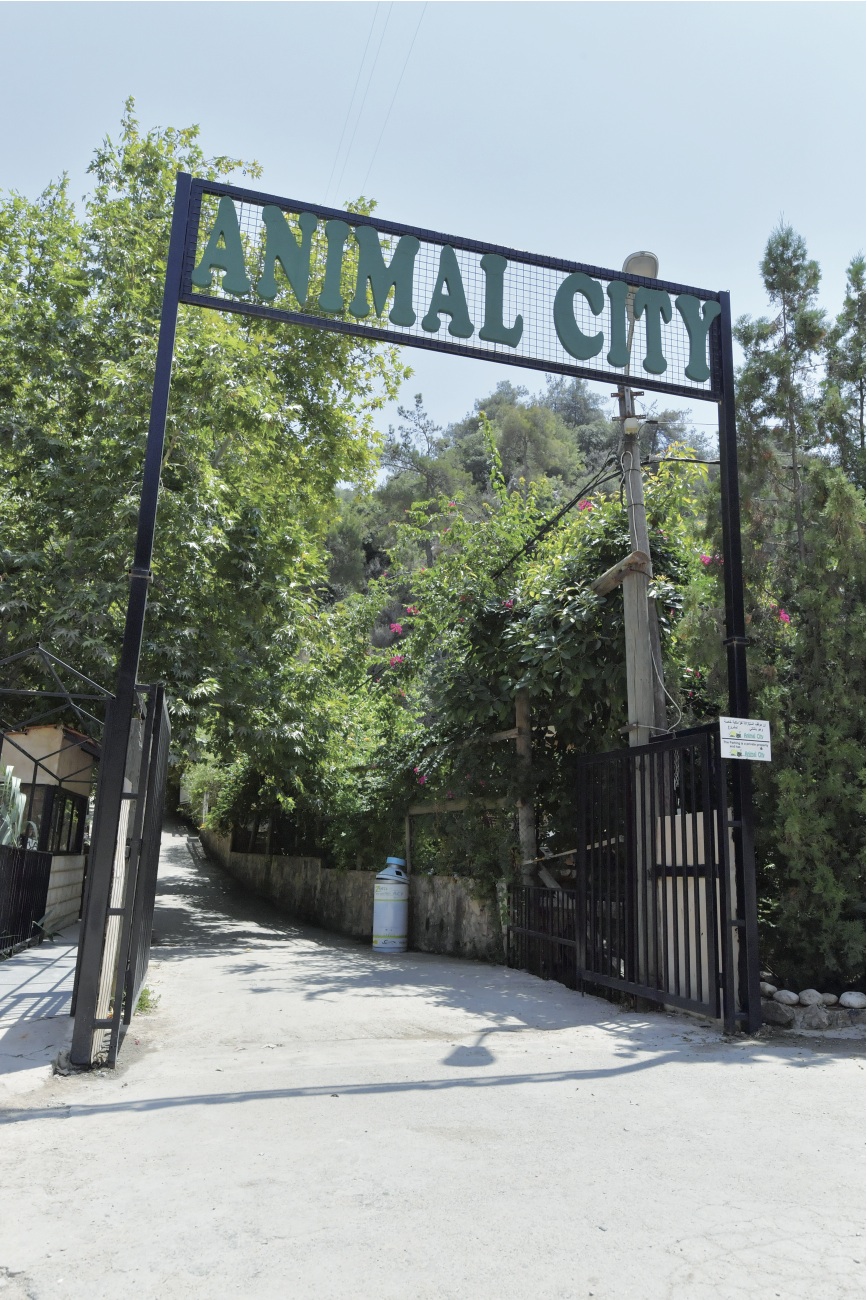

Animal City only recently registered as a zoo with the Ministry of Agriculture (Photo credit: Greg Demarque)

Jeremy Arbid

Jeremy Arbid is an energy and public affairs analyst specializing in Lebanon’s oil and gas industry. He was formerly a journalist covering economics and government policy for Executive Magazine in Beirut. His experience includes roles as a policy specialist in Chicago and with the United Nations in Geneva. Jeremy holds a Master's in Public Administration from the American University of Beirut and a Bachelor's in Political Science from Hamline University.

1 comment

I’ve been to this zoo and came out heart broken. The conditions are appalling. I hope the zoo closes down and the wild animals go back to wild life. How the hell do you have the audacity to place a lion in a small cage where he can barely move?? These people need to be locked up in cages to get a taste of their own medicine. If there is any petition to be signed or anything to be done to close it down or come down harder on animal abusers, I’m all in.

Comments are closed.