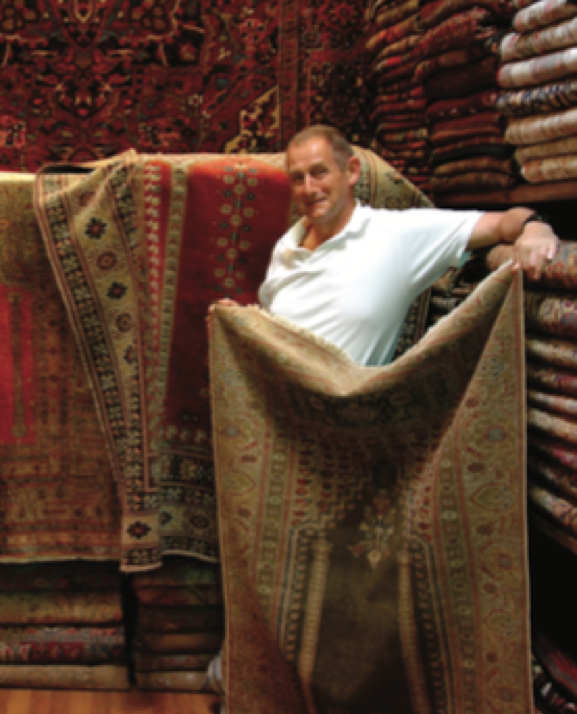

Peter Grimsditch

Journalist, editor, and author Peter Grimsditch’s career began at his college's student publication and led him to become the founding editor of Britain’s Daily Star. He later worked in New York and Turkey as as a correspondent, eventually becoming the No. 2 editor at Lebanon’s Daily Star before inheriting the editorship.