The industrial sector in Lebanon is often regarded as the runt of the economic litter. Real estate, tourism and banking receive the lion’s share of attention and praise, not to mention political support. Perusing the figures over the past five years showing the manufacturing sector’s inexorable decline in share of value added to gross domestic product(GDP) — in comparison to other sectors of the economy — it is easy to see why attention is focused elsewhere.

Nassib Ghobril, head of economic research and analysis at Byblos Bank, holds firm that Lebanon’s industrialists are actually faring rather well, however. “The sector is doing well, and we shouldn’t always be putting it down saying it is on its way to disappearing and that industry is not in good health,” he said.

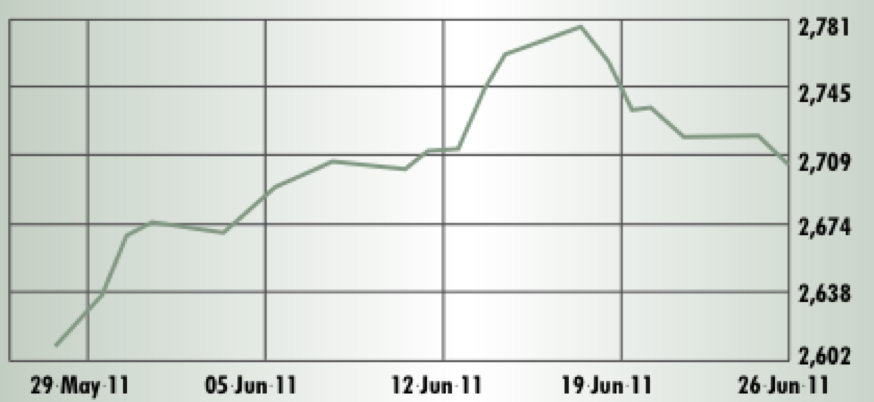

Indeed, when judged on its own merits, and not in comparison to other sectors of the economy, industry has proven resilient in recent years. Imports of industrial equipment — a good indicator of industrial activity —have increased by a compound annual growth rate of 9.2 percent over the past decade. What is more, the value the sector has added to the economy has increased at an accelerating rate, from 1.5 percent in 2001 to 11.3 percent in2009.

A rocky road

But this growth has not been without its blips. If anything, the vicissitudes of the local and regional political arena over the past decade have highlighted industry’s acute responsiveness to security concerns. The long-term nature of investment in the industrial sector means it is one of the first areas where investors get cold feet when the all-too-common specters of discord rear their ugly heads.

“They [industrialists] don’t want to borrow in a market where there is a lot of uncertainty and where cash flow is a major concern, especially when you have political concerns,” explained Jad Chaaban, acting president of the Lebanese Economics Association.

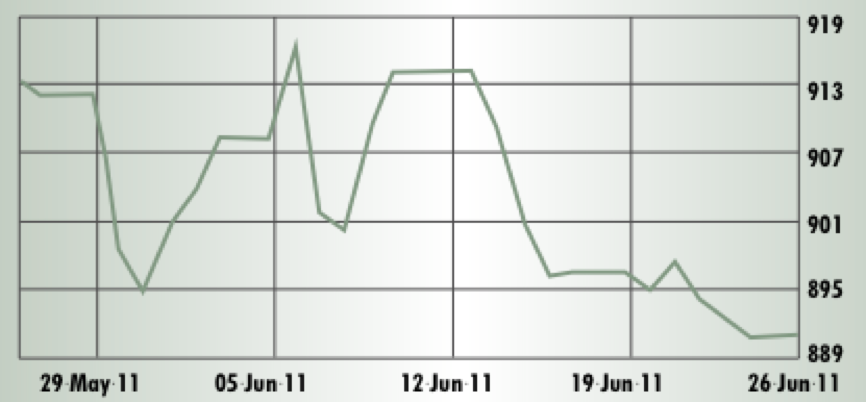

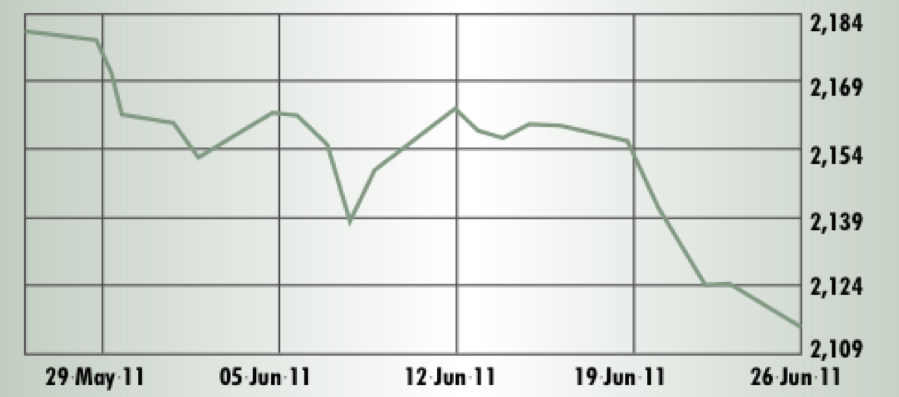

At the close of 2010, industrialists had good reason to hold their heads high after a strong performance throughout the year. Industrial exports were up 27 percent on 2009 and imports of industrial machinery and electrical equipment hit a record high of $227 million, up 14 percent from2009. In fact, industrial exports have been increasing consistently and strongly for most of the past decade — excluding 2008-2009 during the international financial crisis and a slow down following the 2006 war — with the prepared foodstuffs, machinery and mechanical appliances, pearls, precious and semi-precious stones (excluding gold ingots) and base metal sub-sectors performing consistently well.

But 2011 has ushered in upheavals in Lebanon and across the wider region, with events in Syria remaining the most pressing concern for Lebanon, and how the chips will fall is still far from certain.

Head of the Council for Industrial Exports’ Development Khaled Farshoukh fears the consequences for Lebanese industry. “There has been growth of around 20 percent to 25 percent every year [in industrial exports in the last three years],” he said. “When we compare that to the first quarter of2011 we can see there is no growth… When we look to the figures, if we don’t move up we will lose.”

His concerns are warranted — especially as imports of industrial machinery and electrical equipment also stagnated in the first quarter — but it is still too early to assess the impact of the recent regional turmoil on Lebanese industry. Heading into the second quarter, industrial exports were up 16.76 percent in April 2011 on the same month in 2010.

The new Minister of Industry Vrej Sabounjian told Executive, “I encourage Lebanese businesses to see this as an opportunity to search for new markets if theirs in the Middle East have been affected. It presents new challenges and new opportunities.” Beyond the creation of a stable and secure environment for investment, few Lebanese industrialists have high expectations of support from the government. General Manager of Dalal Steel Industries Toufic Dalal said, “people nag about the government. I don’t nag because if you compare between Lebanon and other countries — in Europe, for example, — you would pay 40 percent to 50 percent tax, but here I only pay 15 percent [corporation] tax. It offsets the costs we have to endure.”

Basic requests

But low expectation for services does not mean no expectations.

Ghobril from Byblos Bank reasoned that a “15 percent corporation tax is low, as is the capital gains tax, but that doesn’t excuse the government from providing basic services like electricity, roads and water. The very basics at least. Not to mention security. If the government can’t deliver these basic services it should not exist.”

Addressing the perennial saga of Lebanon’s debilitated energy system is one of the ‘basics’ where industrialists concede they need government support. “This is a very big problem… There is no clear government policy for the energy sector,” Farshoukh said. “Until now everyone is still working on diesel and there are no alternatives. So if there isn’t a push from the government to have a special price for diesel for industry we will continue to have the same problems.”

A 2010 report by the Ministry of Industry states that in 2007 industrial spend on energy from Electricité du Liban amounted to 1.3 percent of intermediate consumption — the cost of the inputs of production — which is proportionally not particularly high. However, because electricity supply is not constant, industrial establishments spent $192.3 million on fuel products for their own energy production, which constituted 4.1 percent of intermediate consumption. Additional costs to industrialists stem from disturbed production and increased depreciation of equipment, according to Chaaban. “The major cost for industrialists is the interruptions. The indirect cost is the replacement of the machines that are hit by these interruptions,” he said. A 2008 World Bank report states that the average industrial firm loses7 percent of its sales value due to interruptions in electricity supply.

The government could also foster a more propitious environment for industrial development with the creation of a well-designed and managed network of industrial zones. These would be designated areas of cheap land for industrial firms with the suitable infrastructure on site to provide a microcosm with lower operational costs [see Q&A with Neemat Frem on page94].

Industrial zones do already exist but they have failed to provide industrialists with the infrastructure or land price incentives to relocate.

In the late 1990s, the Investment Development Authority of Lebanon composed a strategy to encourage the migration of industrial firms into the zones but it was beset with difficulties. According to the Ministry of Environment’s “State of the Environment Report 2000”, almost 88 per cent of all industrial establishments in Lebanon in January 1999 were located outside of the 72 industrial zones in the country.

The issue is a sticking point for the new minister, however, as indicated by its inclusion in the new cabinet’s ministerial statement. The government “will also create a committee to administer industrial centers and look for industrial zones”, it says, and Minister Sabounjian confirmed to Executive that the issue of industrial zones was a top priority for the new cabinet. However, details on when the committee would be established, and its makeup, were not forthcoming.

Chaaban expressed trepidation at the expressed interest. “Every government program says, ‘We want to have industrial zones throughout he country’, but nothing happens. The problem is that those in charge are still driven by financial interests linked to the real estate and banking sectors.” Minister Sabounjian countered, saying “There is a great environment here [in the cabinet] and an atmosphere to do together what needs to be done for this country, especially in the Ministry of Industry. I feel the ministers are pro-industry; for the first time in a long time this government is pro-industry.”

But the jurisdiction and budget of the Ministry of Industry remains relatively limited; in 2010 its budget allocation was approximately$5.8 million, just 1 percent of the total for the general works and transport ministry and less than 10 percent of the agriculture ministry.

If Minister Sabounjian is going to execute his policies to stimulate the industrial sector he will need to enlist the support of several of his sister ministries. This should be easier with a somewhat unified cabinet, which needs to show it can deliver on its policy promises. However, first some concrete policies and plans need to be developed, which are at present woefully lacking in substance.

United we stand

There are clearly several infrastructural hurdles that need to be surmounted to improve the competitiveness and profitability of Lebanese industry. However, when firms do decide to invest, access to finance and capital is, generally speaking, readily available. According to Neemat Frem, president of the Association of Lebanese Industrialists (ALI), “this is not a problem at all”.

In 2007, $165 million in interest-subsidized loans were provided to the industrial sector, which constituted 67.2 percent of all such subsidized loans given that year. In fact, every year from 2004 to 2007 the industrial sector received more than 50 percent of offered interest-subsidized loans, which come through a number of channels, including the Banque du Liban, Kafalat, the European Investment Bank and leasing companies.

But while access to loans, often at discounted rates, is nota problem for Lebanese industrialists, Chaaban argues the reluctance of Lebanese family-run businesses to consolidate and open up their capital is a hindrance to growth in the sector. “There has to be some kind of consolidation. Until now it’s very family-oriented small units and it’s inefficient,” he said. “If you go to Dora and Bourj Hammoud everybody is producing the same products.” His assessment is supported by a 2007 Ministry of Industry study, which reported 78.2 percent of industrial establishments employed between five and 19workers.

Byblos Bank’s Ghobril pointed to the failure of private equity schemes to take root in Lebanon as an example of the reticence among Lebanese industrialists to open up stakes in their companies to outside investors. “The capital is there and the expertise to manage private equity funds exists in Lebanon, but family businesses are reluctant to open up their capital to institutional investors,” he said. “They prefer to go with their own internally generated funds or with loans, even though it is more expensive to borrow.”

Director General of the Beirut Chamber of Commerce Rabih Sabra argued that the predominance of small firms was due to the entrepreneurial spirit of the Lebanese, which in itself is a strength and a driver of growth. However, in a changing climate of increased competition, he added that consolidation in some sectors may be inevitable. “It will come when they feel there is competition, and companies from abroad are getting parts of the market. It’s a slow process but I hope that Lebanese companies realize that they can’t compete if they don’t merge and create partnerships,” he said.

While most people acknowledge certain sectors of industry would certainly benefit from more consolidation, opinions diverge on whether this needs to come from market incentives alone or if the government has an encouraging hand to play.

ALI’s Neemet Frem argued that while large is not always preferable to small, some sectors, such as agro-industry, would benefit from more consolidation. What is more, he will be campaigning for new laws and policies to incentivize mergers, including assistance with relocation costs, tax holidays and social security benefits.

Minister Sabounjian conversely reasoned that market forces alone should provide the incentives for firms to merge while the government keeps its nose out. It is a safe bet to say that devising policies to encourage greater consolidation will not be on the minister’s to-do list any time soon.

Keeping the edge

So, while Lebanese industrialists may be trundling along in the shadows of the economy’s power-house sectors, they should still be given credit for their tenacious toil. But fresh challenges and opportunities lie ahead for them. In recent years Lebanon has entered into a number of bi- and multi-lateral trade agreements, and trade liberalization is likely to continue in the coming period; Lebanon is still intent on joining the World Trade Organization.

As barriers to trade come down and protectionist measures are removed, Lebanese industry will clearly have to overcome a number of internal and external obstacles to remain competitive and thrive on the international stage.

The government is going to have to get its act together and provide industry with the stability and infrastructure that will encourage investment and lower operating costs. And, for their part, industrialists are going to have to show flexibility to adapt to the changing climate in which they will be operating, and when necessary abandon the ‘I’m the keeper of my castle’ mentality.