The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) is under threat. We know this because the only country to have ever used nuclear weapons (twice) told us last month. The warning came at the end of a two-week meeting of the 106 NPT member nations in Geneva in early May. A statement from the five sanctioned nuclear powers — the United States, United Kingdom, Russia, France and China — laid responsibility for the threat of increased nuclear proliferation squarely on Iran and North Korea. Yet a quick look at the record shows those most hysterically calling for an international effort to ‘shore-up’ the NPT have long worked to undermine the world’s premier weapons control agreement — at least when it comes to their own obligations.

Although the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty is generally understood in the West as giving the United States the right to decide who can and who can not have nuclear technology, the document’s exact wording is a little more complicated. At the heart of the agreement is a quid pro quo arrangement, one the West (primarily the US) has long failed to uphold. In return for forgoing nuclear weapons, nuclear power for civilian use is to be made available to all non-nuclear signatories. And yes, this does include Iran.

On top of this, under Article VI of the NPT, the five recognized nuclear states are obligated “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.” This requirement was strengthened via a 1996 International Court of Justice ruling which unequivocally stated nuclear powers must disarm. It was further reinforced at the NPT Five-Year-Review in 2000 when delegations from 180 countries (including the US, then under Bill Clinton) agreed on a 13-step program to implement Article VI.

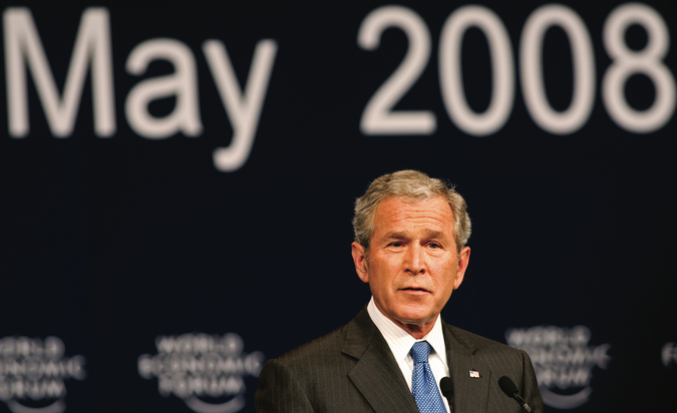

Yet this most essential element for a workable NPT has been delayed, ignored and outright breeched by Western powers for years. The Bush administration in particular has demonstrated a unique determination to ensure NPT obligations apply to everyone but the United States. This was clearly displayed in 2002 with the release of the US Nuclear Posture Review. In that document America reaffirms the ongoing role nuclear weapons will play indefinitely in her defense policy, outlines the research and development of a number of new tactical nuclear weapons such as bunker busting bombs and, for the first time, shifts the use of nuclear weapons from deterrence to first use, a radical departure in military policy which received little press attention. All of which effectively ends a US commitment to the NPT.

Moves by the United States to reduce its nuclear arsenal also need to be taken with a large grain of salt. In another little publicized but extreme shift from convention thinking on disarmament, the Bush administration has done away with the principle of irreversibility in terms of reducing its nuclear weapons stockpile. While the average person may understand disarmament to mean actually destroying your nuclear weapons, the legal eagles of the Bush administration have ruled this clause simply means putting them on standby. Under the 2002 Moscow Treaty — a key agreement the White House cites as evidence it takes its Article VI obligations seriously — the US is not required to destroy its weapons. Rather, they simply must not be “operationally deployed”, meaning a large number will be maintained in a “responsive force” capable of redeployment within weeks or months.

Furthermore, the NPT is only one of many overlapping pieces of legislation which work together to control the world’s most destructive weapons. Its main supporting pillar is the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, an agreement which prohibits nuclear test explosions (or any other) and one which America has steadfastly refused to ratify for more than 10 years. The other major piece of complementary legislation is the negotiation of a treaty banning the production of any further fissile material, the fuel for nuclear weapons. Again, the conclusion of such an agreement has been stymied by Washington. In November 2004, the UN Committee on Disarmament voted in favor of a verifiable fissile materials cut-off treaty. The result was 147 in favor and one against. No prizes for guessing who opposed. Likewise, US support for the nuclear programs of Pakistan, India and Israel makes its near daily hubris against Iran ridiculously hypocritical.

The US is right to assert the NPT is under threat. International Atomic Energy Agency director general Mohamed ElBaradei summed the treaty’s main challenges as follows: “We must abandon the unworkable notion that it is morally reprehensible for some countries to pursue weapons of mass destruction yet morally acceptable for others to rely on them for security and indeed to continue to refine their capacities and postulate plans for their use … We have come to a fork in the road: either there must be a demonstrated commitment to move toward nuclear disarmament, or we should resign ourselves to the fact that other countries will pursue a more dangerous parity through proliferation.”

John Dagge is a freelance journalist based in Syria.