The US subprime crisis is having little impact on the Middle East financial sector; in fact the crisis turned out to be quite an opportunity for the region’s financial institutions. To date, the only direct loss reported was by Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank (ADCB), which wrote down $19 million in assets during the third quarter of 2007. A few other firms took indirect hits. One such firm was Emaar Properties. In August 2007, the Dubai-based property developer explained that its US subsidiary unit John Laing Home’s (JLH) third quarter results were lower than expected due to the subprime mortgage crisis and a possible implosion of America’s housing bubble. Emaar was unable to comment on this development for Executive. In a previously conducted interview with Reuters, however, Emaar Property’s chief financial officer, Amit Jain, noted “third-quarter JLH results are going to be lower than earlier estimates — not incurring losses, but profits won’t be high.” News of lower returns for JLH hurt Emaar Properties, as it posted its first decline in profit in the last three years. Its share price dropped to a 28-month low as investors sought out less-exposed options.

This decline came in sharp contrast to the optimism felt by Emaar in 2006 when they purchased JLH for $1.05 billion. While it finalized the deal before mass subprime defaults occurred in the later half of 2006, some analysts did question the rationale behind the decisions to acquire JLH as talk of a US housing bubble made its way into the media. Although American real estate woes have ultimately taken a toll on Emaar Properties, other regional institutions have avoided the same fate because of different asset allocation abroad and a strong domestic market.

Gulf property markets do not appear threatened

The subprime crisis does not appear to threaten Gulf real estate and Gulf investors remain confident in their domestic housing markets. In December 2007, the Khaleej Times noted that the subprime crisis would not hit the UAE’s property sector. The CEO of Rakaa Property, Abdulrahman al-Tassan, explained in the article that the Emirates’ property market has better standards than those in the US. To insure against defaults, the Gulf country makes sure underwriting standards are strict and borrowers undergo background checks before they are issued credit.

Banking on better days

Gulf banks also found themselves in safe waters. Banking institutions keep diverse portfolios in high-grade investments to mitigate risk, ensure positive returns and minimize the risk of defaults. They are also supported by high liquidity and government willingness to intervene if investments turn sour. Standard and Poor’s credit analysts Emmanuel Volland and Mohamed Damak found in a recent study only limited exposure by Gulf banks to US subprime mortgage-related instruments.

The study investigated 20 Gulf banks with the largest exposures to subprime mortgage-backed securities and found that less than 1% of total assets were exposed. Other indicators, such as total exposure to subprime mortgage-backed securities as a percentage of total equity were higher, nearing 10%, but the report took an optimistic tone, saying banks are not exposed enough to warrant any changes in policy, as long as all their subprime exposure remained in equities of high investment grade with ratings of ‘AA’ and ‘AAA’. In an interview with Executive, the analysts maintained that Middle East banks’ exposure to subprime securities is still investment grade.

Still, not all banks have had consistent performance during the subprime crisis. Bahrain’s Gulf International Bank (GIF) saw its Moody’s rating drop from stable to negative on its A2/prime – 1 deposit ratings and A3 subordinated debt ratings because of the bank’s holdings of US mortgage-backed securities. GIF can choose to either change its procedures to bring its ratings back to stable or it can ignore the rating and maintain this exposure to subprime-related securities. Moody’s decision is not likely to have a significant impact on Bahrain as most Gulf banks are supported by governments willing to bailout beleaguered firms and banks.

In step with the US Federal Reserve

Although exposure remains low, Gulf banks and institutions are not moving forward as smoothly as they would in the absence of the subprime debacle and the ensuing credit crunch. The credit crunch is putting recessionary pressure on the US economy, which is currently being countered by the US Federal Reserve. All economies that peg their currencies to the dollar are affected by the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy. The list includes most Gulf countries, except Kuwait, which depegged its currency from the dollar in 2007. The six countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council have begun implementation of the Gulf Common Market (GCM) agreement and are preparing for a common currency to be minted in 2010.

The Federal Reserve’s main short-term worry since the apex of subprime defaults in October 2006, is that a recession in the US might follow resulting in far-reaching implications abroad. To preempt this, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is set to grow the economy through a series of interest rate cuts. The interest rate cuts are an attempt by policy makers to encourage lending by making money cheaper to borrow. Firms will, it is hoped, borrow rigorously and thereby promote economic growth. The Federal Reserve cut interest rates to the lowest level in two years when they hit 4.25 % in late 2007. Then on January 22, 2008, US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke cut rates again to 3.5%.

The Gulf will have to follow suit, either by changing their pegs or by altering monetary policy to match the US changes. To maintain parity with the dollar and keep regional investors from engaging in interest-rate investment arbitrage on the US market, the central banks of the region must lower interest rates in turn. Although some of the greenback-pegged Gulf economies have revalued their currencies to the dollar, they will also continue to maintain the peg to keep parity with each other’s currencies until the GCC common currency begins.

According to chief economist and head of research at Jadwa Investment, Brad Bourland, Saudi Arabia’s currency peg to the dollar means that Saudi must echo US interest rates. If the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency allows too much divergence between interest rates, investors will capitalize on the widening spread. Bourland also noted the harm interest rate cuts may have in encouraging inflation in a region that does not need to see any more of it.

Keeping prices and currencies happy

Gulf countries are battling double-digit inflation, because the Fed’s interest rate cuts are putting expansionary pressure on their economies. To counter the pressure, some Gulf central banks have decided to raise their reserve requirements, exercising one of the few sovereign moves the region’s central bankers have left. By raising reserve requirements, the central banks are constricting the economy by keeping more money in the vault and less in the hands of borrowers. Qatar, which is battling 15% inflation, raised its reserve requirement by 50 basis points to 3.25%, which will force banks to stash away more of their capital with the central bank, leading to a contraction in the economy. The move will counter growth without disrupting Qatar’s interest rate parity with the greenback.

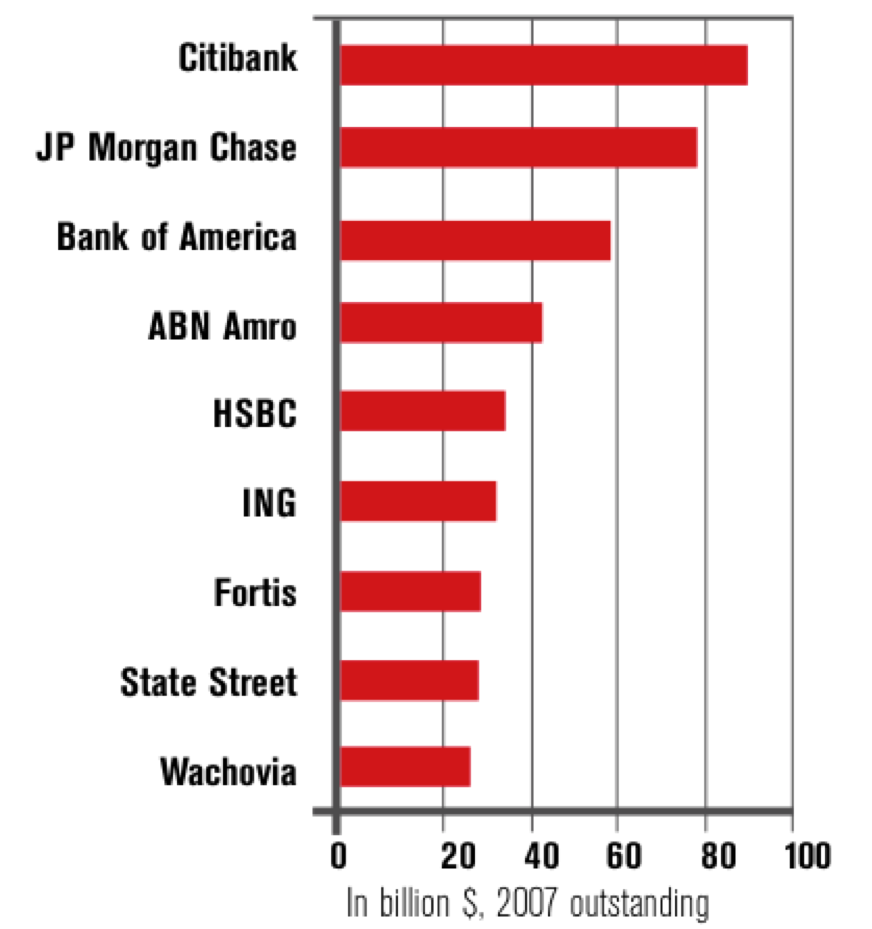

Potential Bank Liabilities

Top bank sponsors of commercial paper, 2007

When can the bonds start?

As Middle East central banks follow the increasingly active moves by the Fed to lower interest rates, many firms waited to issue bonds, opting instead to do so once the spread narrows, because bond valuations based on current spreads are likely to be undercut by reactionary interest rate cuts.

According to Dr. Eckart Woertz, program manager of economics at the Gulf Research Center, the main impact of the subprime crisis in the Middle East “has been the widening spreads and assets [that] have been affected. The financing condition is deteriorating, even for companies and issuers.” Looking forward to 2008, he noted that, “There are a lot of potential [bond] issues in the pipeline. Should markets calm down, then they will come to market. It tells of confidence in a fledgling bond market.”

Recent moves include the UAE’s Dana Gas postponement of a $1 billion Islamic bond issuance (sukuk) and Bahrain’s Ithmaar, which delayed sales of their five year bonds valued at $300 million. Abu Dhabi First Gulf Bank also postponed issuing its $3.5 billion Eurobond. Those who went ahead during a market with high spreads lost big. Among them was the Saudi Basic Industries Corp. (SABIC), which had aimed at raising $2.7 billion from a bond issue. In the end, they were only able to obtain $1.5 billion.

Middle East money saves Wall Street

The major players in the Middle East, in particular the Gulf, are the government-owned and operated sovereign wealth funds (SWF). In terms of the subprime crisis, these SWFs may come out on top as willing and able financiers, providing much needed liquidity for Western firms and banks. In January 2008 both Citigroup and Merrill Lynch solicited the help of sovereign wealth funds from Asia, including the Gulf.

In total, these funds manage as much as $2.9 trillion and have invested in everything from telecoms to aerospace. However, their entrée into the banking world has been the most impressive. According to a January 2008 report in the Economist, since the start of the subprime mortgage meltdown Gulf-based SWFs have shifted almost $69 billion into Western investment banks. As the magazine notes, “They have deftly played the role of savior just when Western banks have been exposed as the Achilles heel of the global financial system.”

The largest SWFs include the the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority with $875 billion in assets, various Saudi Arabian funds at together $300 billion, Kuwait’s Reserve Fund for Future Generations ($250 billion), Libya’s Oil Reserve Funds and the Qatar Investment Authority (both $50 billion), and Algeria’s Fond de Regulation des Recettes ($42.6 billion).

The common thread among the MENA funds is that the controlling governments are rich in natural resources, whether petroleum or natural gas. With recent oil volatility working to the region’s benefit, sovereign wealth funds have excess liquidity to diversify long term investments abroad and to provide the credit needed in US markets.

In 1991 Saudi Arabia’s Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal bought $590 million worth of shares in Citicorp. Now those same shares would be worth $5.36 billion. With today’s Citigroup offering 7% dividends on shares bought by the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) and others, it is easy to understand why during fallout of the subprime crisis they did not have to go looking for investors. These appealing terms are coupled with the fact that potential investors were fully briefed on the group’s upcoming forth quarter announcements and share prices are half of what they were last summer. In fact, Citigroup is well positioned to raise even more money from SWFs in the region should upcoming earnings reports bring more bad news, as is expected.

Future trends for sovereign wealth funds

In a report on Sovereign Wealth Funds and Bond and Equity Prices Morgan Stanley’s chief UK economist David Miles explained the difference in the amount of risk sovereign wealth funds are willing to take when compared to more traditional strategies. He suggested that because SWFs have vast assets, their investment patterns display a high tolerance to risk. In comparison, the wealth of more traditional governments is invested in foreign exchange reserves and most of that is sunk into low-risk, low-return instruments like government bonds. Miles added that the unusual appetite for risk and the eminent growth of sovereign wealth funds will likely have an impact on the degree of risk tolerance for investors the world round. He noted that should this occur, there ought to be a resultant effect on asset prices.

GRC’s Woertz noted that sovereign wealth funds “… have a lot of money. They have a serious liquidity problem in the sense that they have too much money. They have problems finding investment opportunities for their liquidity, so they will buy in the US but also in other places. They are not satisfied with just buying treasuries anymore.”

Citigroup’s losses prompted a $12.5 billion cash infusion from SWFs like the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA). This large cash infusion had been preceded by one in November 2007 from the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority worth $7.5 billion. According to the International Herald Tribune, Citigroup Chairman Robert Rubin had made an eleventh-hour trip to secure the KIA funding. However, the bailout might work to the advantage of Gulf investors. If Citigroup’s shares are now at their low point, then its new Gulf investors will benefit in the long term. And the Citigroup deal is not the only one in the making right now. In December 2007 Zurich-based bank UBS received $1.8 billion from an anonymous Middle Eastern investor.

The following month Merrill Lynch saw share sales to the tune of $6.6 billion, bought by various entities in the region including Saudia Arabia’s Olayan Group, the Qatar Investment Authority and the Kuwait Investment Authority.

Where does the region go from here?

The subprime fallout has not caused any disruption on the Middle East markets, nor has it significantly damaged regional firms or banks. What the subprime crisis brought was a credit crunch desperate for foreign liquidity. Regional firms and banks are beginning to fill in the gap. Only in recent weeks have Western bankers begun to realize that Gulf liquidity is going to provide their cash-strapped markets with the funds needed to rejuvenate business projects and economic growth. Bailout by a mixture of institutional and personal investors for both Citigroup and Merril Lynch is just the beginning of a future trend by sovereign wealth funds and petrodollar beneficiaries to supply the capital demands of US and Western markets.