The Egyptian American comedian Ahmed Ahmed says in his stand-up show that, because there is a supposed terrorist also called Ahmed Ahmed, his name is in a most-wanted list. That makes air travel a unique — if not, horrible — experience. But one cannot but laugh when he tells of his ordeal: “I always know who the air marshal is on the plane. He is the guy reading People Magazine upside down and looking right at me.” After googling his own name and finding out that indeed there seems to be a terrorist called Ahmed Ahmed, the comedian wonders if the other Ahmed is in the Arab world going through the same identity mix-up: “I swear I am not a comedian, I am a terrorist!”

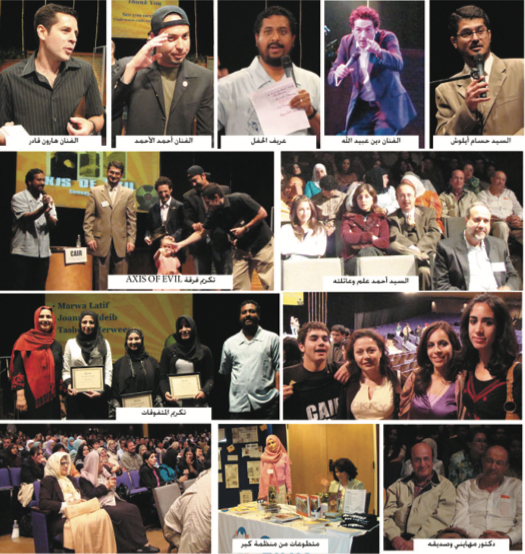

These and other stories are told by the Axis of Evil, a stand up comedy group formed by Ahmed, Aron Kader (whose father is Palestinian and mother is an American Mormon), Maz Jobrani (Iranian-American) and Dean Obeidallah (Palestinian-American). Of all places, the Axis’s first performance happened where the expression Axis of Evil has a whole different connotation: Washington, D.C. Since then, November 2005, they have been touring America using humor as a weapon against prejudice. Now, after full-house performances throughout the US, the Axis is touring the Middle East with a mission that is as necessary as destroying prejudice: helping make the Arabs laugh at themselves.

In America, the Axis of Evil Comedy Tour has been welcomed with raving reviews by the likes of CNN, Time, National Public Radio, and Newsweek. Along with the laughter, the group aims at promoting a shift in cultural perceptions. “We don’t want to be defined any longer by the worst examples in our community. There are a few terrorists and they define all of us,” said Ahmed in an interview on CNN.

But the paradigms are changing already. A lot has happened since 9/11, when Dean Obeidallah followed the suggestion of a club owner and dropped his Arab surname, performing under his middle name instead, Dean Joseph. Now, the group has become so popular and is so successful in defying prejudice that one of the Axis’s show in the US was sponsored by one of the main targets of the jokes: the FBI. With some of the officers attending one of the performances, Ahmed looks at them, sitting close to the stage, and tells the audience “It’s so nice to be standing in front of the FBI and not be handcuffed.”

In his routine, Ahmed reminds the audience that after 9/11, hate crimes against Middle Easterners increased by 1,000%, but that still leaves them in fourth place among hate crime victims — behind blacks, gays and Jews. “I just want to be number one in something,” he joked. United in prejudice, but with the wisdom to transform pain into pleasure, the ethnic comedians are more important in healing and unifying than they are given credit for. Quoting a colleague who is a rabbi, Ahmed says “you can’t hate anybody when you are laughing with them.”

But do Arabs easily laugh at themselves? Kader has one line aimed at the more uptight, imitating a fictitious Arab who insists he does indeed have a sense of humor: “Whoever says we don’t have a sense of humor, I will kill you and burn your flag.” But it takes a lot of high self-esteem and intellectual freedom to laugh at oneself. The only practicing Muslim in the group, Ahmed jokes that “you know you’re a Muslim when you drink, gamble and have sex but you won’t eat pork.”

Comedy is about stereotypes. As a Brazilian, I know my country has them in abundance and I was genuinely offended when my government threatened to sue the producers of the Simpsons cartoon, after one episode showed the Simpson family travelling to Rio to find out what happened to the money they were donating to a boy living in a slum. On the same trip, the Simpsons watch TeleBoobies, a show in which semi-naked girls entertain Brazilian children, while the Brazilian public transport system is depicted as one long conga line. Sadly, even our president at the time made the surreal comment that the cartoon “brought a distorted vision of Brazilian reality.”

Since when does comedy have the duty to reproduce reality? What some suspect, though, is that the president was offended not by the distortion, but precisely by the small bits that didn’t distort our reality all that much. After the embarrassing, irrelevant dispute, Homer Simpson made his retribution in style. In a later episode, he is the proud owner of a monkey. And he asks his friend to be careful with the animal, as it was a present from Brazil, and whose pedigree is very important, since “this monkey is the cousin of the tourism minister.” Kudos.