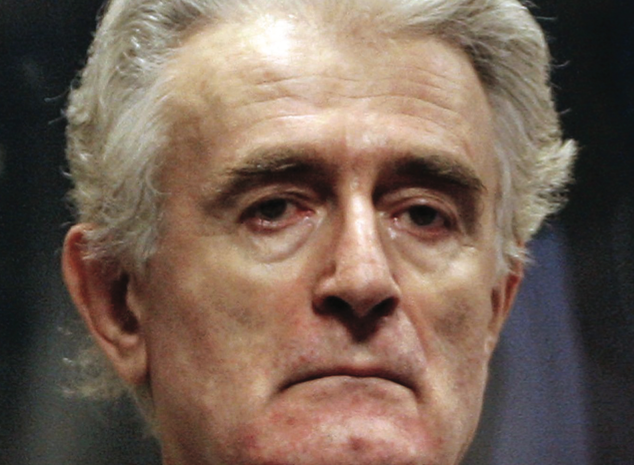

Michael Young

Michael Young is a senior editor at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut and editor of Diwan, Carnegie’s Middle East blog. Previously, he served as a contributing editor at Executive magazine in Lebanon. Young also worked as opinion editor and columnist for The Daily Star newspaper . He writes a biweekly commentary for The National (Abu Dhabi) and is the author of The Ghosts of Martyrs Square: An Eyewitness Account of Lebanon’s Life Struggle. Young holds degrees from the American University of Beirut and the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.