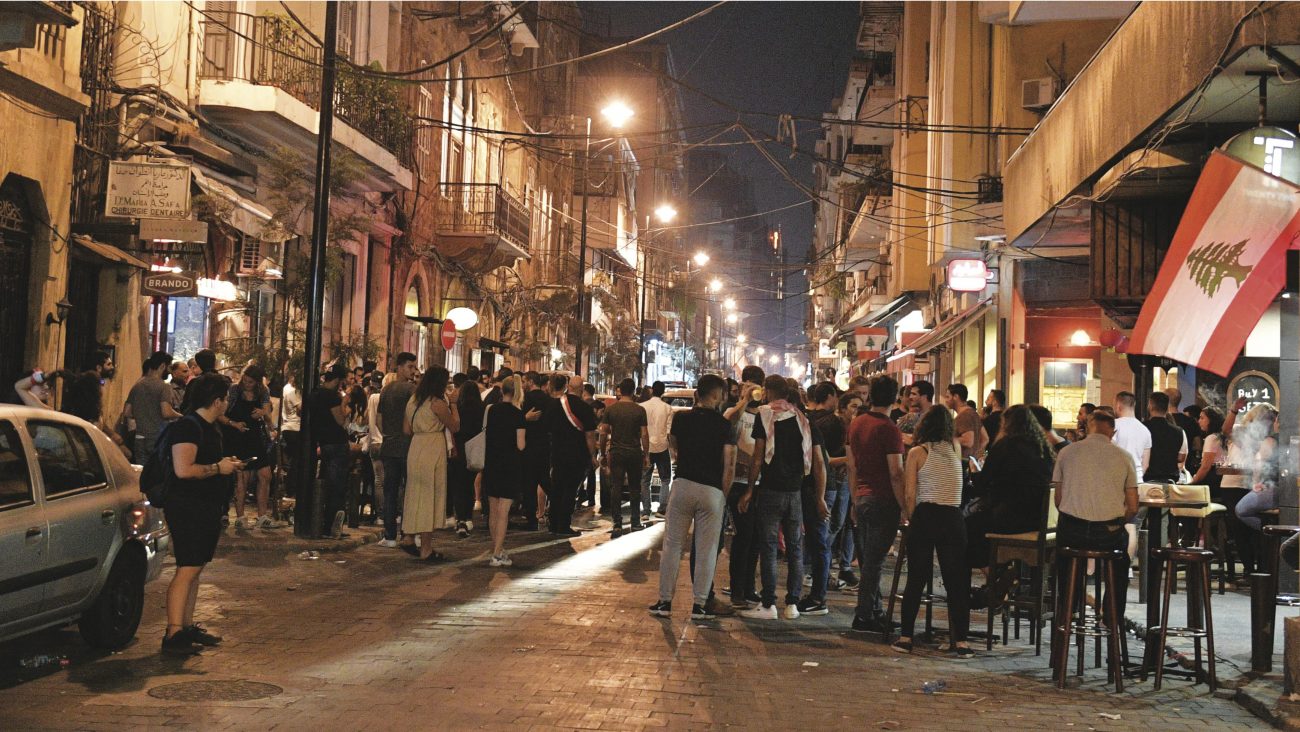

Lebanon’s F&B operators face an economic crisis and low tourism

written by Nabila Rahhal

Nabila Rahhal

Nabila is Executive's hospitality, tourism and retail editor. She also covers other topics she's interested in such as education and mental health. Prior to joining Executive, she worked as a teacher for eight years in Beirut. Nabila holds a Masters in Educational Psychology from the American University of Beirut. Send mail