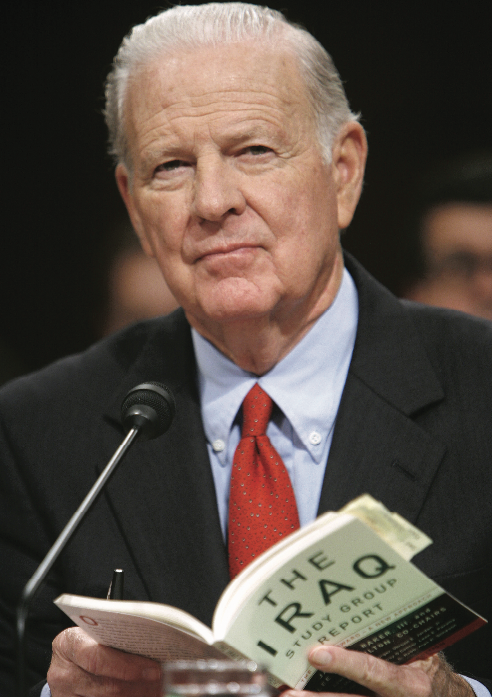

As every upper level manager knows, you bring the consultants in to buy you some peace and quiet with the shareholders while you’re deciding whether the buy-out clause in your contract turns out to be more lucrative than the year-end bonus. So why did George W. Bush, the Harvard Business School-educated CEO of the United States of America, let the consultants get all the headlines? After the mid-term elections, all anyone could talk about in Washington was the Baker-Hamilton Iraq Study Group.

Leaks from the ISG provided the press with plenty of cannon fodder, as conservative publications went on the offensive against Baker, the man who handed Lebanon over to Damascus, and let Saddam stay in power to become the symbol of anti-Americanism in the region. White House critics on the other hand called it the end of the Neoconservative project in the Middle East, a return to a “mature” Middle East policy, managed by the Bush family’s long-time fixer. Savvy insiders wondered if the formation of the bi-partisan group was some clever plan of the president’s to make the Democrats equally culpable for the meltdown in Iraq. And everyone wanted to know if the study was likely to become the blueprint for American foreign policy.

In the end of course, it was all much ado about nothing, as Bush acted like a proper CEO and tossed the report in the garbage. Jim Baker shouldn’t give up his day job, one White House wag remarked, putting an end to weeks of speculation: the President still makes American foreign policy. And yet after the Democrats won both houses of Congress, and polls show an American public increasingly dissatisfied with Bush’s Iraq strategy, the major question still lingers: what is this president’s foreign policy?

Bush’s legacy rests entirely on Iraq. The problem is that it is precisely this large Arab state that is preventing the White House from seeing how much the ground has shifted during the last four years, partly due to Iraq itself, but largely just because the region is always highly volatile.

After September 11 the Americans were mad at the Sunnis, especially Saudi Arabia. It was Riyadh after all who had provided, unwittingly or not, much of the staffing and financing for the largest terror attack in history. Part of the idea then behind the invasion of Iraq was to rearrange the regional balance, thereby empowering the Shia. But four years after the fall of Saddam’s regime, the US’ major problem in the region is not Sunni jihadism, but the Islamic Republic of Iran. Tehran is at war with the US, and is fighting American allies, interests and troops throughout the region.

The key to understanding this new regional alignment of course is not Iraq, but Lebanon. Israel’s war against Hizbullah drew the lines very clearly, and now Jerusalem is reportedly offering the Saudis a chance to re-affirm the casual alliance contracted during this past summer. Ehud Olmert intends to meet with Saudi officials to kick-start the moribund peace process. Does that mean that a comprehensive peace deal between the Israelis and Palestinians is finally in the offing? Of course not. The point of the exercise is to take the Palestinian file away from Hamas’ Iranian and Syrian sponsors and return it to the Sunnis.

So, if Israel and the traditional Sunni regimes have lined up under Washington’s umbrella, why doesn’t the US know it? Because of Iraq. If the White House sides with the Sunnis, the Shia will make it impossible for US troops there. And thus, the White House is caught in a strange bind – it knows that pro-Sunni policies in the rest of the Middle East will affect its standing in Iraq, but cannot yet admit it is impossible to detach Iraq policy from a larger strategic vision.

And it’s not just the administration that’s stuck; the Baker Study Group is the clearest manifestation of this confusion about the region. James Baker is as close to the Saudis as any other living American and the Saudis obviously do not want the US to engage Syria and Iran. And here he is putting forth advice – withdrawal from Iraq to leave the Sunnis at the mercy of the Shia, while “talking” with Iran and Syria – which would undermine an ally whose vital interests, at least in this case, are perfectly in line with Washington’s: to maintain the position of the US in the Persian Gulf.

The fact is that the Bush administration, its critics and enemies have greatly misunderstood the nature of American power. Remember that Osama Bin Laden said the US was a “paper tiger” because it was flushed out of Vietnam, Beirut, Somalia, etc., and hence Bush says he will not “cut and run.” So what is next? To prove to an obscurantist fanatic like Bin Laden that it is the earth that revolves around the sun and not the other way around?

It is easy to see how the US has failed in Iraq, and it is equally easy to forget the degree of difficulty involved. In a matter of months, the US brought down two troublesome Middle Eastern regimes, and only a country as rich and powerful, capricious and arrogant as America could afford to believe it was in the interest of the world to democratize these places as well. That 150,000 US troops and scores of American diplomats could not bring Jefferson to the land of the two rivers describes the limits of a missionary vocation, not power. So, what is the point in saving Iraq if it costs Washington the world – or worse, American hegemony in the Persian Gulf?

Lee Smith is Hudson Institute visiting fellow and reporter on Middle East affairs