There is a wide debate in Lebanon about economic eform in the context of the implementation of the decisions of the CEDRE conference and the conditions set by donor countries. The economic reform program suggested by the government of former Prime Minister Hassan Diab addressed a series of measures aimed at modernizing the economy and stimulating growth, including privatization and market liberalization. The new government formed by Prime Minister Najib Mikati is promising to involve the private sector in the services previously led by the public sector, to include electricity, telecommunication, and the likes.

Privatization aims to reduce the cost of services, improve their quality, expand their scope, increase

investments, give impetus to economic growth and stimulate the participation of citizens and the private sector through ownership of shares in privatized services’ sectors.

Of course, raising the issue provokes different reactions in political, economic, trade union, and popular circles. From welcoming and supportive, to conservative and opposing. If business circles declare their absolute support for such proposals, for example, some components of civil society may openly declare their opposition and rejection of any privatization process, and demand the restoration of previously privatized economic sectors that could provide large revenues to the state, calling for absolute adherence to the role of the public sector as a pioneer and guarantor of justice and conditions necessary for economic and social advancement. What are the reasons for raising the issue of privatization in Lebanon? What are the expected results of the privatization of some sectors?

PRINCIPLES AND OBJECTIVES OF PRIVATIZATION

The main objectives of privatization go beyond providing income to the treasury to deal with the public debt and, in our present case, contribute to securing the funds needed to rebuild what was destroyed. Experts unanimously agree to position the consumer’s interest and the necessity to secure public service to its best terms at the top of the pyramid of privatization goals. Most of the countries that adopted privatization aimed, in the first place, to improve the level of services provided by a publicutility or to try to address what was tainting this utility as a result of its mismanagement by the public sector. In this context, we can cite the successful experience of LibanPost, which brought about a qualitative revolution in the field of postal services

in Lebanon, yet did not bring in any direct income to the Lebanese Treasury. A public utility has exceptional powers as it is owned by the state and managed by its institutions. In most cases, these powers are monopolistic, leaving the consumer with no choice but to comply with the conditions set by the utility. In such cases, if service delivery is insufficient or unsatisfactory, privatization comes in to allow legitimate competition in the field of those services, thus giving consumers the benefit of choosing reduced costs or improved services. In the US electricity market, for example, consumers – especially industrialists – are able to choose their electricity provider (state-owned or private) based on prices traded in the Electricity Exchange. Answering most of the questions related to privatization must be done for each utility separately, in a way that dispels the fears of both citizens and experts. The ideal approach is to examine the required legal frameworks and mechanisms in order to guarantee simultaneously the interests of the state and those of consumers, in addition to determining the economic feasibility of the privatization process.

REGULATORY AUTHORITIES

Any privatization process imposes high financial burdens on the state, especially in the preparatory stage. These expenses are often consultative and non-refundable, and aim at setting up the necessary mechanisms and legal frameworks as well as ensuring the feasibility of the privatization process. The use of some of these funds to establish regulatory bodies (a regulatory authority or committee) constitutes a smart investment for the state, whereby these bodies can advise the privatization process, in addition to monitoring the proper functioning of the public utility and taking up various other technical and administrative roles. Conferring the appropriate authority to these regulatory bodies is essential; regulators should operate according to high transparency standards and enjoy the necessary autonomy to carry out the expected work in a serious and effective manner. Therefore, securing strict legal and administrative bases are vital. These foundations should be comprehensive and cover all angles, from the mechanisms of appointing the members of these regulatory bodies to defining their powers, in order to ensure the greatest degree of impartiality and to guarantee the continuity of their operation. Protecting those bodies from any interference should start with the process of appointing its members, all the way to granting them the power of decision-making and the ability to carry out their duties in the face of opposition from partisan politics, as long as they act in compliance with the law. Determining the role of these bodies, whether advisory or supervisory, is a key factor in the stability of the privatization process and an important incentive to attract serious investors. The main role of regulatory bodies remains monitoring the operation of the privatized facilities, especially ensuring compliance with the terms of reference and securing healthy competition and preventing monopolistic activities. These bodies also help establish a financial monitoring mechanism to maintain the flow of the state’s sporadic resources. Most countries have adopted the “quality-of-service” criterion as a basis for evaluating the work of the public utility and the services provided. However, this criterion must be based on specific, clear, and precise points to avoid negligence in this area, which is often at the expense of the economically weaker party, i.e. the consumer.

Some may view the establishment of regulatory bodies for all sectors intended to be privatized as a costly and futile endeavor, since the advisory role can be assigned to private bodies, and over- sight remains in the hands of the guardianship authority, i.e. the responsible ministry. The role of control as part of tasks inserted to the regulatory body has several benefits, whether in terms of the experience of its members, or in terms of ensuring the integrity of the institution, with all due respect to successive ministers. Virtually all the necessary paperwork and studies have been prepared to establish three essential regulatory bodies for Lebanon (See box ), yet partisan political interference still prevent them from starting operations or engaging in the process of appointing members.

In order to reduce expenses, several countries have adopted the so-called “unified regulatory authority”, meaning that the regulatory powers of different sectors are entrusted to a single administration. In the case of Lebanon, however, the best solution seems to lie in the establishment of three regulatory bodies:

A Telecommunications Regulatory Authority will supervise any privatization step in the telecommunications sector, including cellular and international communications.

An Energy Regulatory Authority, whose powers include electricity, water and oil, will draw the main lines for privatizing electricity production, including electricity from renewable energies.

A Transportation Regulatory Authority, whose mandate includes transport, roads, and public works. This authority is entitled to look into the feasibility of constructing some highways or bypasses, regulate shared transportation, and study the possibility of privatizing the Beirut Port and other ports in whole or in part.

There can be no privatization without the appropriate regulatory body. The Lebanese have paid the price of haste and demagoguery in the telecommunications sector twice, the first time when cell phone licenses were granted in Lebanon, and the second time when these licenses were with- drawn. The management contracts in that case lacked any vision for the future and did not solve the problem of the monopoly of telecommunications by a few players who dictated their conditions to the Lebanese for almost two decades and wasted large amounts of money that our economy desperately needed.

A discussion with experts in electricity, fuel, and renewable energy organized by Executive Magazine In partnership with Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. The roundtable focused on Lebanon’s energy crisis, sustainable solutions and recommendations to reform the sector and achieve national commitments to reduce emissions.

Dreaming a bright (lit) future

In the most optimistic view (please note: a rarer commodity than real money), there will be a future in Lebanon that is powered up by utility-scale wind farms and solar photovoltaic installations. There also will be smart cities, Internet of Things, Real Intelligence (artificial or other) and yet-to-be-discovered grand innovative green technologies that harness the powers of the sun, wind, water, and earth. There will be decentralized and well-regulated industrial, commercial, and agrisolar projects that are sustainable, social, and profitable.

There will be communal universities, public hospitals, free schools and digitized infrastructures that rely on renewable energy (RE). There will be governance in municipalities that cherish public goods, and households that contribute to the nation’s energy safety and are at the same time energy efficient and almost self-sufficient. Everything electric will be highly energy efficient and fully integrated into the stabilized national power grid with diversified, professional, fair, and corruption proved administrative structures in generation, transmission, distribution, and collection.

The electricity bill will come to me on time, be detailed and explicit for its climate balance, and affordable. The country will be part of a responsible world powered by RE. Net-zero will be a forgotten term, as will be carbon trading. There will be no COP Summits, nationally determined commitments (NDCs), and other irksome and meaningless code words that obfuscate the insufficiency of polit-babblers, technocrats, and bureaucrats of all nations. There will be no deforestation and no heavy methane emissions. Hashish will globally be legal and consumed responsibly. There will be cedars on all hills and mountain ranges of Lebanon.

The only remaining question will be if this Lebanon will be a village built by our talented expats in the Kingdom of Far, Far Away or on a planet where people from this country have settled in a galaxy far, far away.

It is November, not April Fool’s. Ergo, while we dream distant dreams of stable electricity and have visions of prosperity and peace, the balance sheet of the Lebanese struggle for renewable energy presents a mixed bag of nice and ugly. There are unmistakable upsides to the ongoing adoption of RE and a massive argument in the realization that renewable energy is not a green choice or nice sustainable opportunity for the people in this country. Passionate World Bank observers and Lebanese experts are in agreement that the people and government of Lebanon have no choice but learn to trust RE (and each other). In this sense of trusting RE, Lebanon by sheer lack of alternatives, is now proceeding on a path to climate sanity and sustainable energy safety that the world at large seems to be hesitant to walk, taking, as shown again this month at a key global climate debate, three or more fast steps back for every five slow steps forward.

Good steps announced at the Glasgow COP 26 UN summit presumably were pledges to stop deforestation and reduce methane emissions significantly by end of 2030 end rein in coal by 2050. These mesh positively with plans for gigawatt offshore wind island projects and many innovative RE applications in national strategies in Europe as well as net-zero goals by nations and corporations.

On the side of hesitancy to act as fast as rational calculations on climate threats suggest, however, are the estimates that the global target for keeping the temperature increase below the 1.5 degree threshold looks to be missed badly. These are coupled with the clinging to coal and oil by countries that benefit from exploitation of fossil resources, the historic knowledge that past climate risk mitigation pledges have rarely been fulfilled and that the increase of temperatures has not been slowing, and the fact that the targets against deforestation and methane output that countries just pledged to for 2030 would better be achieved by 2025.

But additionally it seems warranted to account for some unrecognized assets and overlooked advantages that Lebanese RE plays have going for them.

ALL EQUAL UNDER THE SUN?

Renewable energy has been a passion of leading minds in local academia and private sector for forty years, as the Lebanese Solar Energy Society proudly testifies. Abundant tomes on the role and potential of RE have been written in Lebanon.

RE is not only for the rich. In the currently overheated retail market for solar PV, the top ten percent of households with the right combination of quality awareness and financial means are seen by quality-focused providers as the addressable market for sustainable home systems. Those who opt in are going to be long-term winners of the new reality where no sane person on earth, however socially privileged, can afford waste of energy.

But solar technology for simple needs is becoming more technically capacious and much cheaper. Systems have already been implemented in several thousand poor homes where they run lighting and phone chargers; a new generation system will be powering a small fridge. Solar PV in Lebanon is viable part of social safety net development.

Not to mention that the empowerment of institutions and the public goods infrastructure of Lebanon, oft neglected in the past, is being sped up. According to the Lebanese Center for Energy Conservation, 122 public schools have active plans to go solar. Soldiers guarding the Lebanese border against smuggling and intrusion from isolated posts in the no-man’s-land are beneficiaries of solar PV installations. Our hospitals, schools, universities, and our military are on their way to install RE with the help of international partners and global organizations.

Our SMEs can benefit from energy efficiency and RE programs to leave behind a wasteful pattern where they faced reduced international competitiveness because they were hooked on subsidized state power with a costly overlap with private generators while being deprived of the knowledge and incentives to become as energy efficient as they could be. Our industries, agro-industry and agricultural producers have in recent years learned many new things about RE. They have been prepared by these painful lessons and now stand eager to tap into new efficiencies and new income streams whether through industry-scale installations, net-metering, or wheeling options.

Preventing the melting

At this time of the greatest need for renewable electricity and indeed any electricity, it is finally to note that Lebanon has not only lost billions in electricity subsidies and payments for inefficient fuel that have amounted to, literally, burnt money. We have also incurred massive opportunity costs.

These costs are visible when one talks to RE companies and individual practitioners in the fields of solar PV and energy conservation. It is not only that Lebanese RE companies in the past two years, those firms that did not vanish from the market in everything except perhaps for their name, website, and listing in an un-vetted registry of RE providers, have relied for their economic survival on incomes from projects in Egypt, Ghana, and elsewhere in the region. As everyone in this industry confirmed to Executive when asked, Lebanese RE companies are able to compete outside of Lebanon, sometimes in very crowded markets. Especially when noting that Lebanese engineers are familiar with complex challenges in design and execution of electricity solutions from the smallest to the industrial scale and beyond – perhaps among the world’s most adapted to intermittent supply and multiple and changing electricity supply challenges. This competitive advantage might have been leveraged into a much stronger RE industry on regional scale.

Also, as a more recent opportunity cost, the RE sector has seen the outmigration of talented engineers and experienced technicians, “en masse” as one industry insider says, while the supply of new talent, the addition to national human capital, is hampered by the problems that the tertiary education sector is confronted with.

Finally, we cannot but emphasize that all steps toward RE and energy safety are, to a large or even critical extent, contingent on people’s behavior changes, the political will of elected (presumed) servants of the people, and restoration of the financial system.

Executive calls for speedy adoption of the relevant laws (Updated Law No. 462 and the draft Distributed Renewable Energy), the establishment of a functioning regulatory authority, and the incentivization of industrial and commercial scale solar PV projects. We support initiatives and plans to create new structures for transmission and distribution of electricity, and join with all the loudness that we can muster in calls for the creation of energy safety and affordable RE all over the country without opportunities for theft, extortion, and corrupt profiteering in the electricity sector to the detriment of the public good.

And while we make every effort to rescue the Lebanese economy and install incremental units of RE for next year’s electricity need, with the full use of our considerable talents and great networks of friends and diaspora, our human and social capital, let us remember that we humans need to dream. We can function without money and electricity for a week because we find a way to do so, but we cannot function without working towards our dreams.

Left in the wind for now

In February 2018, the Ministry of Energy and Water, representing the Government of Lebanon, had signed Power Purchasing Agreements with three wind farm developers for the development, installation, and operation of wind power generators in the Akkar region with a cumulative capacity of wind power of 226 MW. According to the terms of the agreement, the first units of power produced by these projects were supposed to be injected into the national electricity grid, and not a moment too soon, considering the current state of the electricity sector in the country.

Sadly, the project was delayed and has not seriously kicked off to date. The present financing difficulties make it unlikely it will resume unless outside funding is secured.

If the project were to be carried out, it would generate more than 800 million kWh of power annually, enough to power 200,000 Lebanese homes, operating over the hills and ridges of Akkar. It would employ in excess of 600 people during the construction period, mostly comprising local talents and skills, and provide stable rent incomes to dozens of landowners and several municipalities over the 20-year period of the agreement.

A VISION BLOWN IN THE WIND

Against all odds, the plan was, and still is, to build a state-of-the-art power generation project in one of the most pristine areas in Lebanon: Akkar. We, as developers, dreamt big. In addition to the wind farm, our vision includes an eco-tourism attraction that celebrates the history of the region and integrates hopes for the future. This consists of a leisure and educational hub that brings people from all over the country. A learning center offers resources to schools and community groups, as well as educational activities. The site also includes 40 kilometers of biking trails, as well as multi-purpose graded trails built from the recycled waste generated during construction are intended for picnics, sightseeing, and events planning.

Yes, it is a mega infrastructure project but one with a clear and beneficial social and environmental footprint.

Unfortunately, that did not happen. By end 2019, and after the project had secured early on letters of intent from international supporting financing parties, the abrupt financial meltdown occurred, with its devastating consequences on all levels, consequences with which we are all too familiar.

Where do we go from here? Shall we, as private sector investors call it quits? Shall we give up after preparing all the necessary studies and investing vast amounts of money to de-risk the electricity sector in Lebanon, to secure the necessary land for the wind farm project and keep them secured even up to this day?

ACTION NOW

There is no question about it: Lebanon needs power desperately. We are ready to resume our enterprise. Give us stability and the wind farms will be up and running in 18 months.

What is needed for this?

Immediate action and at a large scale. We need to move ahead with renewable energy projects. This is not limited to wind farms but also includes solar power projects.

Ideas for financing are always available if we think collectively outside of the box. Carol Ayat, a respected energy finance professional and investment banker, has presented an innovative plan in that regard (see story page 40). Her paper on a new funding model to finance electricity projects across generation, transmission, and distribution deserves serious stakeholder discussion. Her win-win proposal opens up the possibility for depositors in the Lebanese banking sector to invest their “lollars” in such projects. The central bank Banque du Liban (BDL) would swap these “lollars” with part of the remaining hard currency it still holds to finance these projects.

Another idea worth considering is for the Government of Lebanon to explore the possibility of using part of the International Monetary Fund’s newly allocated Special Drawing Rights to Lebanon to provide either soft loans and/or the necessary guarantees for such projects to get financed. By that scheme, the Government would invest this money and achieve returns on it.

We need to vamp up renewable energy. We need to start and finish the wind farm project we started eight years ago.

A moment in the sun

Over the last couple of years, Lebanon has become most notorious for its electricity sector. The country has struggled to keep the lights on since the civil war, and has hit its worst milestone with a complete blackout in October 2021. On its own, the state-owned company Electricité du Liban (EDL) has never been capable of satisfying national electricity demand, wreaking the havoc the country now faces. While Lebanon depends directly on fuel imports as a means of energy production, EDL accounts for reported yearly deficits of around $2 billion. The company is also subject to global oil price fluctuations, feeling the impact of the global energy crisis in the third quarter of 2021, as well as government caps on oil purchases, which directly and indirectly impact the national economy. Relying less on oil and gas imports and more on renewable energy (RE) sources, particularly solar energy, will manage to reduce Lebanon’s alarming balance of payments deficit and prevent further blows from market shocks, due to the fact that RE is largely a domestic source of energy.

In March of 2019, the Lebanese parliament ratified the Paris Agreement under law 115. Lebanon committed to covering 30 percent of its energy consumption from renewables by 2030, requiring the installation of 4,700 MW of renewable energy projects, namely solar, wind, and hydro.2 Such projects would reduce the electricity costs by around 50 percent, as well as lower pollution levels, create jobs, support rural development and eco-tourism in remote areas, and spur economic and industrial growth thanks. They would also allow Lebanon to achieve energy security and stability. This idea presents itself today as a solution independent of institutional reforms. This idea stems from Lebanon’s sunny climate which provides around 3,000 hours of sunshine per year, and should be mainly focused on solar energy, which in terms of costs for production is estimated at around $0.04 – $0.05/kWh for utility scale projects; and around $0.07 – $0.08/kWh when storage (batteries) is included. By comparison EDL’s average production cost, comes out to around $0.14 – $0.16/kWH. The demand for solar energy has already increased by factories and companies, with the aim of reducing electricity costs.3

Decentralization and irradiation

Usually when discussing solar power, people often refer to photovoltaic (PV) cells, the black panels that are attached to the roofs of houses or are used in solar farms. This type of solar panel is composed of a layer of N-type silicon and P-type silicon with a conductor linking them; however, efficiency can vary greatly. Traditionally, running conventional power cables from a central source such as EDL towards remote areas is an expensive ordeal, and approximately 30 percent of electricity generated is lost during transport. Solar power; however, can be distributive which means households, schools, hospitals and/or municipalities can install panels and run cables only the short distance to the inside. In rural areas, for example, the cost of solar energy becomes cheaper and more efficient than centralized power sources.4 Solar PV is already an established sector in Lebanon with a decent number of competitive private companies adopting it. The growth potential remains significant. The International Renewable Energy Agency’s (IRENA) Global Atlas for Renewable Energy indicates that annual average solar irradiation in Lebanon ranges between 1,520 kWh/m2/year and 2,148 kWh/m2/year, with most regions being above 1,900 kWh/m2/year. Based on this, IRENA estimates a potential utility scale solar PV of 182 GW.5

In addition to its lower cost and ability to ensure energy security, solar energy has the potential to enable local development and boost innovation in rural areas and across the country. Installing solar and other kinds of renewable energy projects requires well situated land, areas such as in Hermel, Ras Baalback, Tfail, the Chouf, Rachaya, Aqoura, and Taraya. These regions are some of the poorest in the country, and allowing for Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) projects to take place in these regions would help their development, a study conducted by the Lebanese Foundation for Renewable Energy (LFRE) found that approximately 2,700 permanent jobs can be created from RE projects, with two thirds in underdeveloped areas. Moreover, Lebanon’s reliance on highly polluting fossil fuel plants has caused a series of environmental and health problems on the national level. Needless to say, neither the people nor the environment are reaping any benefits from this.

As the country plunges deeper into economic collapse and with the long foreseen energy crisis now here, renewable energy technologies offer the prospect of stable and clean power and heat systems. Solar energy in particular will not only reduce the national budget deficit by decreasing fuel imports, it will also ensure greater stability and energy security, benefiting the country on the economic and social levels. To reap its benefits at this critical period in Lebanon’s history, necessary steps need to be taken in order to support the uptake of renewables.

Solar Energy: A Solution for Lebanon

Levant Institute for Strategic Affairs (LISA)

Lebanon needs to take advantage of the current power crisis to move towards decentralized energy production and reform EDL at the technical and administrative level. Major recommendations mentioned in the LISA policy note to kick-start solar energy uptake include:

• Allocating part of the $1.135 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) allocated by the IMF towards investment in solar energy projects through dedicated solar energy funds.

• Developing a conducive policy environment that will contribute to capitalizing on the use and benefits of solar energy. To date, no permits for Independent Power Producers (IPPs) have been given by the government to build utility-scale projects and these permits need to be issued ASAP.

• Installing solar panels on the rooftops of school buildings as a means to support the education sector. A study6 conducted by the Lebanese Foundation for Renewable Energy mapped 2,561 educational buildings and found that installing solar PV on their respective rooftops would generate 455 MW of clean energy. The government should use part of the SDRs to build solar PV installations on school rooftops in order to guarantee an education for Lebanese children and evade any future fuel crisis the country might face.

• Utilizing existing micro grids of back-up generators to scale-up solar energy on the short term. Given their extensive network and efficiency when it comes to supply and cost, the existing micro grids hold significant potential in being used for solar energy. If these generators along with their grids were to be bought out and transferred towards the municipality, there is potential for further investment. Currently, municipalities cannot take loans to scale up these investments. Therefore, laws linked to decentralization to allow municipalities to undertake such projects need to be formulated and implemented as soon as possible.

• Paving the way by the government for smart and clean grid solutions through modernizing and stabilizing the grid. Modernizing the grid can provide greater quantities of zero-to-low-carbon electricity reliably and securely, including handling the intermittency of renewables like solar and wind power. In addition, investment in base load power is a pre-requisite to scale up renewable energy and reach our 2030 targets. This can be achieved with gas-fired power plants or storage if financially efficient.

Amid the worst economic crisis Lebanon is witnessing since the civil war, one could identify two major observations (a positive and a negative one) when it comes to the country’s energy sector, which is considered both a main cause and a major contributor to the financial gap the government is currently facing. The negative one is that Lebanon appeared to be a country running on diesel, across all its vital sectors such as health, telecommunications, transportation and of course electricity (through the private diesel generators). The other, positive observation is that the current crisis has allowed to create a collective awareness among citizens and communities around the importance of renewable energies, and mainly solar energy, as a tool to reduce their reliance on diesel, along with its long-term environmental and health benefits.

Yet, the current almost-complete blackout the Lebanese people are living is not a surprise nor a coincidence, but rather an expected result of the decades-long mismanagement of the sector. Lebanon’s power and energy sectors’ struggles are the result of the fundamental policy inaction that reigns over decades, with under-investment in infrastructure since the late 90’s, a lack of a comprehensive vision of the country’s energy mix, and a deliberate negligence of the potential of renewables energies.

FUEL IMPORTS: A HIGH DEPENDENCE ON FOSSIL FUEL

The MENA region has always been characterized by a high dependence on oil and natural gas to meet its energy needs. Although the region is a major energy producer, many countries are struggling to meet growing domestic energy demand. According to BP numbers in 2019, the Middle East is expected to face an annual increase in energy demand of around 2 percent until 2040, where the power, transport, industrial, and non-combusted sectors will mainly be responsible for this high increase in final energy consumption. Therefore, transitioning to energy systems that are based on renewable energy is a promising way to meet this growing demand, and has started to be implemented in several countries of the region.

Being part of this region, but not as an energy producer, Lebanon has been a major oil importing country for decades, making it economically vulnerable to oil price fluctuations, a matter that severely endangered its prosperity, and has recently caused a severe jump in gasoline and diesel prices completed with a total removal of subsidies.[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””] For years, imported fuels accounted for around 97 – 98 percent of the energy supply putting a huge burden on the state’s budget. The electricity generation sector was, and still is entirely dependent on imported petroleum products, which we lack the foreign currencies to currently buy.[/inlinetweet] In addition, the transport sector is heavily relying on gasoline and diesel, with the absence of a stringent and sustainable transportation sector.

Lebanon’s total primary energy supply in 2018 was 8.57 Mtoe, or around 61.21 million barrels of oil according to the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2020. In terms of the energy consumption by sector, the transport sector dominates accounting for 52 percent, followed by the residential sector (19 percent), and the industrial sector (14 percent). The energy mix is predominantly made up of oil. In 2018, oil held a 95 percent share in the energy mix, coal accounted for 2 percent (mainly used by cement factories), while renewable energies held a share of the remaining 3 percent, including hydropower. Oil sources in the energy supply have always been the key fuel in the energy mix, varying between 92 and 95 percent since 1990.

However, the Lebanese energy strategy is today at a turning point, as the country cannot continue relying on imported fossil fuels that are bought via the dwindling foreign currencies reserves at BDL. The latter has started the process of subsidy removal on oil products earlier this summer, leaving citizens to confront the reality and burden of increasing prices without any social safety net.

According to the Directorate General of Oil (DGO) numbers in 2018, the imported fuel products in the country amount for around 8.5 million tons combining liquefied petroleum products (propane and butane), gasoline (98 and 95), diesel oil, heavy fuel oil, jet fuel, asphalts and petroleum coke. This would account for around $6.2 billion of hard currency, $1.7 billion of which was used as fuel subsidy for Electricité Du Liban (EDL), Lebanon’s national electricity utility, while $2.4 billion were used for gasoline products.

These numbers fell in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, where fuel imports amounted to only around $3 billion, equivalent to 7.7 million tons of products.

LEBANON’S DOWNSTREAM OIL CARTEL IN NUMBERS

The downstream oil operations, by definition, cover the import, storage, marketing, distribution and use of hydrocarbons as well as related infrastructure that is used to supply oil products to the national market.

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]The downstream oil sector in Lebanon is controlled by 13 private companies that import, store and distribute the majority of the fuel products, benefiting from a large storage capacity. [/inlinetweet]The latter allow these importers to manage more than half (or 55 percent) of the distribution stations that amount in total to around 3,100 stations. They also own around 68 percent of the distribution trucks that transport oil products to the several regions. The sector has been governed by the decree 5509/1994 that organizes the several activities across the value chain from import, to storage, transport, and distribution. To date, this decree has never been well implemented or followed.

When adding to those 13 companies the ones working in the gas sector as well as in the cement industry, which both import their own share of oil products, the total number of companies becomes around 18, equivalent to the number of companies operating in France, and way above the ones in Jordan (5 companies) and Syria (15 companies). This large amount of actors for a small market like the Lebanese one makes their alliance and cooperation vital to secure the profit share. Consequently, these companies do not import individually, but rather agglomerate to import the same shipments and then share the quantities to distribute them in the market, reflecting a clear representation of the monopolistic structure of the sector.

The majority of these companies have emerged during the civil war years with the collapse of the country’s institutions. This cleared the way for militias and influential people to evade government controls and started importing from Syria and other countries, benefiting from their control over the coastal cities and its reservoirs. After the end of the war, more autonomy was given to the private sector as of the 2000’s, and these companies expanded.

These 13 companies have a powerful storage capacity, with 7 terminals on the coastline to store petroleum products shared by both private and public sectors. While those imported from the Government are concentrated at the oil installations in Tripoli and Zahrani, the private sector reservoirs, which accommodate quantities touching 500 million m3 (excluding jet fuel), are distributed over seven ports in Dora, Antelias, Amchit, Zouk and Anfeh, Tripoli and Jiyeh. As for the facilities in Tripoli and Zahrani, they contain about 481,000 m3 in the tanks currently in use.

AN INCREASING DEMAND FOR SOLAR-POWERED SYSTEMS

Building on the positive observation the crisis has emerged with when it comes to the importance of renewable energies, the Issam Fares Institute at the American University of Beirut has launched a quick survey in August 2021 with companies working in the implementation of solar projects for households, industrial and commercial activities, in order to assess the increasing level of demand on those solar systems. 20 companies have responded to the survey and the answers have shown that between January and July 2021, those companies have received around 6,700 requests to install solar systems, 516 of which have effectively seen light with a total energy generated of around 7.75 MW. This means that when citizens get to know the real cost of installing such systems, they become reluctant in moving forward, and also that the year 2021 is expected to reflect the most important increase in solar systems’ installations during the past decade.

By end of 2019, the installed capacity of renewables was around 365 MW, including 286 MW of hydropower and a cumulative PV installed capacity of 78.65 MW, according to the Lebanese Center for Energy Conservation’s 2019 solar status report, while the Lebanese Government has announced its aim to reach 30 percent of Renewable Energy by 2030. In June 2020, the latter target was further supported by International Renewable Energy Assocaition (IRENA) Outlook for Lebanon stating that for Lebanon to reach 30 percent, it was to install around 4,700 MW of solar, wind, hydropower and biogas.

A POLITICAL ECONOMY CONSTRAINT TO THE ENERGY TRANSITION

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]Lebanon’s electricity sector is affected by three key challenges that impact the energy transition at least in the short-term, but potentially also in the long-term: weak governance, underinvestment in the supply, and the lack of financial stability.[/inlinetweet] Deep-rooted political economy challenges have heavily weighed on the energy and electricity demand and supply over the past years. Electricity reform efforts do exist mainly on paper without being implemented, and the main question remains: why hasn’t it?

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””] A successful transition to a more open and competitive power market that supports the renewable take-off will further depend on appropriate institutions and structures with clear roles and responsibilities, as well as a robust regulatory framework. [/inlinetweet]A transition towards a more resilient energy system further requires first the diversification of energy supply and energy demand management on the technical side, but also tackling the political economy constraints that would allow the leapfrog towards renewables, namely the oil cartel value chain, and the diesel generators’ market and network, both benefiting from the collapse of the electricity and energy sectors.

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]The energy transition will need to leave no one behind, and innovative political economy tools would allow all social constituencies to take part of it, where a just participation in the energy transition involves citizens’ awareness. [/inlinetweet]Furthermore, the introduction of participatory tools and channels in the energy transformation process could foster acceptance and contribute to fair power dynamics and energy policies.

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]Both policymakers and citizens need to understand the benefits that renewables can offer and recognize how global cost reductions make this technology an interesting alternative to fossil fuels imports as well as diesel power generation. [/inlinetweet]In fact, the cost of solar panels has dropped by 85 percent over the last 10 years.

The old system of dealing with electricity issues has led to the current complete collapse. A way out should consider renewable energies as a centerpiece of energy planning and not just a policy add-on. This cannot be done without a comprehensive system that ensures the proper implementation of renewable energy systems and the removal of existing legal, institutional and political economic hurdles in front of this implementation.

Incentivize to energize

Through its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), approved by Parliament under Law 115 dated 2019, Lebanon has committed to achieving a 30 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Moreover, the policy paper for the electricity sector issued by the Ministry of Energy and Water (MoEW) and approved by the Council of Ministers on April 8, 2019, aims to secure 30 percent of Lebanon’s total electricity consumption from renewable energy (RE) sources by 2030. Achieving these lofty goals seems very unlikely, unless the private sector is incentivized to participate in the generation of such energy.

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]The electricity sector already had to grapple with a difficult financial situation and the high costs of maintaining its production and distribution networks, so it was among the first services to suffer from the collapse of the economy alongside the banking sector.[/inlinetweet] In turn, it directly affected a host of other sectors that rely on electricity, from industry to agriculture, hospitality, media, and banking again. Lebanon’s crippling energy crisis is made worse by its dependency on fuel imports which are threatened by the shortage of US dollar currency. Rolling blackouts that for many years used to last for three to six hours per day, as of May of this year would leave entire areas with no more than two hours of state power a day. The Lebanese increasingly depend on private generator operators that also struggle to secure supplies amid the crash of the national currency and removal of subsidies.

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]The electricity sector breakdown can be attributed to a number of reasons, including a series of seemingly deliberate attempts at weakening the state utility Electricité du Liban (EDL) through apparent mismanagement and corruption. [/inlinetweet]Decree 16878 dated 1964 conferred both administrative and financial autonomy to EDL, giving the public establishment monopoly over the electricity sector by being solely responsible for the generation, transmission, and distribution of electrical energy in Lebanon. This autonomy has been challenged and undermined by political actors since the end of the civil war, weakening the public institution and establishing full dominance by the MoEW, the tutelage authority presiding over it, in addition to delaying key reforms for its rehabilitation.

EDL’s situation already had worsened with the August 4 Beirut Port explosion that destroyed its headquarters’ administrative assets, meter laboratory, vehicles and warehouses, National Control Center, distribution substations, distribution lines, a data center for the billing system, and other assets, estimated at between $40 and $50 million. Only a few substations within the blast radius received minor repairs, but no clear plan has been put forward to rebuild its headquarters or replace infrastructure assets and equipment, all of which require high expenditure that is not currently available, nor has it been for years.

As a result of all the above, power supply has deteriorated to critically low levels and fails to meet national needs. Rural areas are particularly impacted by the lack of access to electricity. EDL has become operationally bankrupt and constitutes a drain on the government’s fiscal resources. This has also affected other power utilities that purchase electricity from EDL, including Electricité de Zahle. In addition to the fact that billing collection is mismanaged, tariffs are too low to cover power generation and delivery costs and the number of defaults on payments or cancelled subscriptions is increasing as fewer households and businesses can still afford even these low tariffs. Power is also widely stolen, compounding the utility’s losses. Finally, [inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]Lebanon is among the very few countries that still rely on heavy fuel for power generation, a material that is environmentally unfriendly and carries serious implications for the health of the population[/inlinetweet] due to its high level of emissions that exceed globally accepted standards.

Failure to resolve the monopoly

The centralized nature of the electricity sector, along with all the problems it suffers from, has become an obstacle to its reform and, most importantly, to allowing investments in RE generation. While privately-owned generators so far continue to ration electricity to households and businesses, their dependence on fossil fuel casts doubts about their ability to maintain operations, or retain a base of subscribers able to afford their fees.

The conversation is logically shifting towards renewables, although it is not a new idea in Lebanon by any means. In 2010, 6.1 percent of Lebanon’s electricity generation relied on hydroelectricity through concessions awarded as far back as the French mandate. RE power is generally considered a reliable clean source of electricity with significant economic, environmental, and social benefits to Lebanon’s economy: a) It reduces our reliance and/or dependence on fuel imports; b) it assists in the balancing of our national budget through the reduction of fuel import expenditures; c) it creates more employment opportunities as renewable energy is able to offer more local employment opportunities per unit size installed when compared to conventional power sources; and d) it improves the health of Lebanese citizens and the resilience of Lebanese natural ecosystems from reduced air pollution and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

The failure to ensure a reliable supply of electricity has led the Lebanese people to resort to alternative individual solutions as they are legally eligible to use renewable energy resources for their own consumption (See Energy Special Report Overview). The existing legal framework encourages this mainly through Article 4 of Decree 16878 that allows producing RE power “for their own consumption and to cover their personal needs only.” Also tapping into Article 4, an Administrative Curriculum (memorandum), based on a Decision of EDL’s BoD (No. 318-32/2011, titled “net metering”), approved a mechanism whereby consumers can inject surplus RE power generated on their premises (and for the primary objectives of fulfilling their own needs for power) into EDL’s grid and be credited, in return, against their consumption of power from EDL. The net-metering mechanism is certified by the MoEW (as the tutelage authority over EDL) and approved by the Ministry of Finance (MoF) (since it has a financial deduction effect) on an annual basis. The approval is subject to annual renewal by both ministries. Moreover Article 26 of the “Regulation of the Electricity Sector” Law no. 462 dated 2002 states that the production intended for private use with power less than 1.5 MW shall not be subject to the authorization.

One of several failed attempts by the Government of Lebanon to restructure the electricity sector and improve its performance on all levels, began with the ratification of Law no. 462 dated 2002. This law aims to establish the Electricity Regulatory Authority (ERA), restructure the electricity sector, and unbundle the energy activities that are currently monopolized by EDL through private sector participation in the distribution and generation. To date, the implementation of Law no. 462 remains elusive, mainly when it comes to the appointment of the ERA, a crucial step to pave the way for private sector involvement. Since 2012, the MoEW, in charge of implementing the law, has proposed amending it to limit the ERA’s independence and maintain the ministry’s control over it.

Because of continuing political interference, other attempts at involving the private sector in producing electricity from renewable sources also met with failure. These projects were categorized as private-public, achieving legal coverage directly through the Council of Ministers (read “political favors”) instead of through an independent regulatory body supposed to oversee technical feasibility and competence. Only a single RE project, consisting of a wind farm, was planned through this private-public model, but it never kicked off due to several reasons, among which the issuance of the licenses in 2017 before bankability acquisition (See Salah M. Tabbara’s article). If the ERA had been in place, no licenses would have been issued unless a competitive portfolio tender, part of the due diligence of the bankability assessment, was completed. The current economic crisis further put an end to any progress on this project.

Laying down the draft

Since there is a lack of a clear legal framework that can provide certainty and incentivize the private sector to invest in RE power, it is necessary to establish a general law that gives all Lebanese economic sectors the opportunity to at least partially reduce their demand on the national power grid, paving the way for further penetration of distributed renewable energy systems equal to or less than 10 MWp.

With the technical, legal and financial support of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Distributed Renewable Energy (DRE) law was drafted, closely involving the MoEW, EDL, and the Lebanese Center for Energy Conservation (LCEC). A steering committee was established in that regard and included representatives from all the mentioned stakeholders. After two years of work and close follow up, the draft law was sent at the end of October 2021 by EDL to the MoEW in order to be circulated to the Parliament through the Council of Ministers.

The DRE draft law complements Law no. 462/2002, covering all technical aspects of distributed renewable energy generation while ensuring no overlapping. It allows and regulates the net-metering process in all its forms and formats in a more permanent way. As per EDL Board Decision no. 318-32/2011, only single owner net metering (one owner, one meter) is currently allowed and is subject to annual renewal. The DRE draft law would also allow meter aggregation for single or multiple owners of multiple meters, even in geographically disconnected areas.

The draft law also allows peer-to-peer distributed RE trading through direct power purchase agreements (PPAs) for up to 10 MW. Through “on-site” direct PPAs, customers can purchase power directly from RE generators who, in turn, can divert excess electricity into the grid through the net metering arrangement. The principle is the same for “off-site” direct PPAs, with the added difference that remotely located generators will need to pay the utility for using its transmission and distribution network through which they deliver RE power to customers.

The law also makes provisions for the creation of a renewable energy department at the utility, until the ultimate goal of establishing the ERA comes to fruition.

[inlinetweet prefix=”” tweeter=”” suffix=””]Realistically, increasing the generation of electricity from RE sources cannot fully replace fossil fuel power generation, but it is a vital backup for the electricity sector, especially now.[/inlinetweet] Individual RE systems are a positive trend but implementing community solutions would constitute a more solid base from which to answer Lebanon’s energy needs. Ratifying the DRE at the soonest would incentivize private sector involvement in not only the generation, but also the distribution of electricity from RE sources. The private sector would shoulder some of the financial and logistic burdens of the national grid, namely when it comes to underserved or remote areas, and begin to end blackouts. It would also help generate revenue for EDL and pave the way to reform, staring with the establishment of the ERA. The combination of all these factors would give a serious boon to Lebanon’s efforts to reach its national RE commitments and improve quality of life in terms of better service and health by reducing emissions.

1. How do I assess my home energy needs?

It is important for the vendor you choose to guide you on assessing the load of how many appliances/ devices you want turned on simultaneously, which would inform your choice of inverter, as well as on assessing and determining your home’s critical load and how long loads could be used for (hours of operation). This would inform your choice of the battery bank size and type (Lithium or Lead-acid). A good way to assess your energy needs is if you have a meter installed to track your current generator’s input. This would be a good starting point, as well as a personal audit on what your home considers a critical load. Critical loads are a selection of appliances or devices that you believe would require continuous energy supply or in other words require back up when the power grid fails. These need to be separated from other loads and connected to a different sub-panel. Non-critical loads are electrical devices connected to the main panel that will not be backed up during grid failure.

2. Can I install Photovoltaic (PV) panels without batteries?

If you have no other choice, you can install PV panels with no batteries, but you will only be able to convert energy directly to your home’s network when the sun is shining and there is now way to store energy.

3. Can I get rid of my diesel generator once I get solar?

While many people would like to install a PV energy system to discard their diesel generator costs, it is unlikely that the solar energy system will secure your home’s continuous and complete energy needs, unless you make a large investment in the battery bank (size and quality).

4. Do you have any installation examples from a home similar to mine?

There are many companies out there now, we advise that the company you choose to install your system can show-case their experience and proven record. Try to make sure that the company you are contacting is specialized in solar PV design and installation.

5. Do you have any references I can call?

If possible, it would be great to ask for references of similar projects installed for other homes that have similar needs to yours.

6. What is the duration of the manufacturer warranties on the different components?

Ask for the duration of the manufacturer warranties of each of the main components. Typically, warranties are up to 25 years for PV panels, 5 years for inverters, 2 years for controllers, 1 year for Lead-acid batteries, and 5 years for Lithium-ion batteries.

7. What type of battery should I go for?

While Lead-acid batteries are widely available and cheaper at first glance, and Lithium-ion batteries are a relatively new technology, there are many factors that distinguish each choice which can help guide your decision. Ask about the space required to store them, the charging time, the ventilation and temperature requirements, the percentage of battery capacity discharged, and compatibility with inverters, all of which directly impact cost.

8. Do you provide after sales services and maintenance?

Make sure the company you select to install your solar system can provide after-sale maintenance and customer support. You will need a yearly checkup after installation.

9. Does the system have local or remote monitoring?

Make sure to ask if the installed system would have a local and/or remote monitoring system. Keeping up with battery use, power-blackouts, critical loads can sound like a lot. However, a good system that is designed around your needs would help you to maintain the system optimally. Remote monitoring systems will help avoid improper care and overuse of batteries which is often a common source for failure in electrical off-grid systems. This is a feature that can help you prolong the lifetime of your system or troubleshooting it when needed.

10. When would the (full) system be up and running in my home?

Last, make sure to ask how long it would take for the entire system to be up and running and get that timeline in writing.

By UNDP Lebanon’s specialist energy team CEDRO, this content is made possible with the support of the European Union.

Check out more resources:

Solar energy starter-kit; 10 things you need to know

6 Myth-busting facts on solar in Lebanon

6 Things you can check right now to see if your residence is eligible for solar system installation!

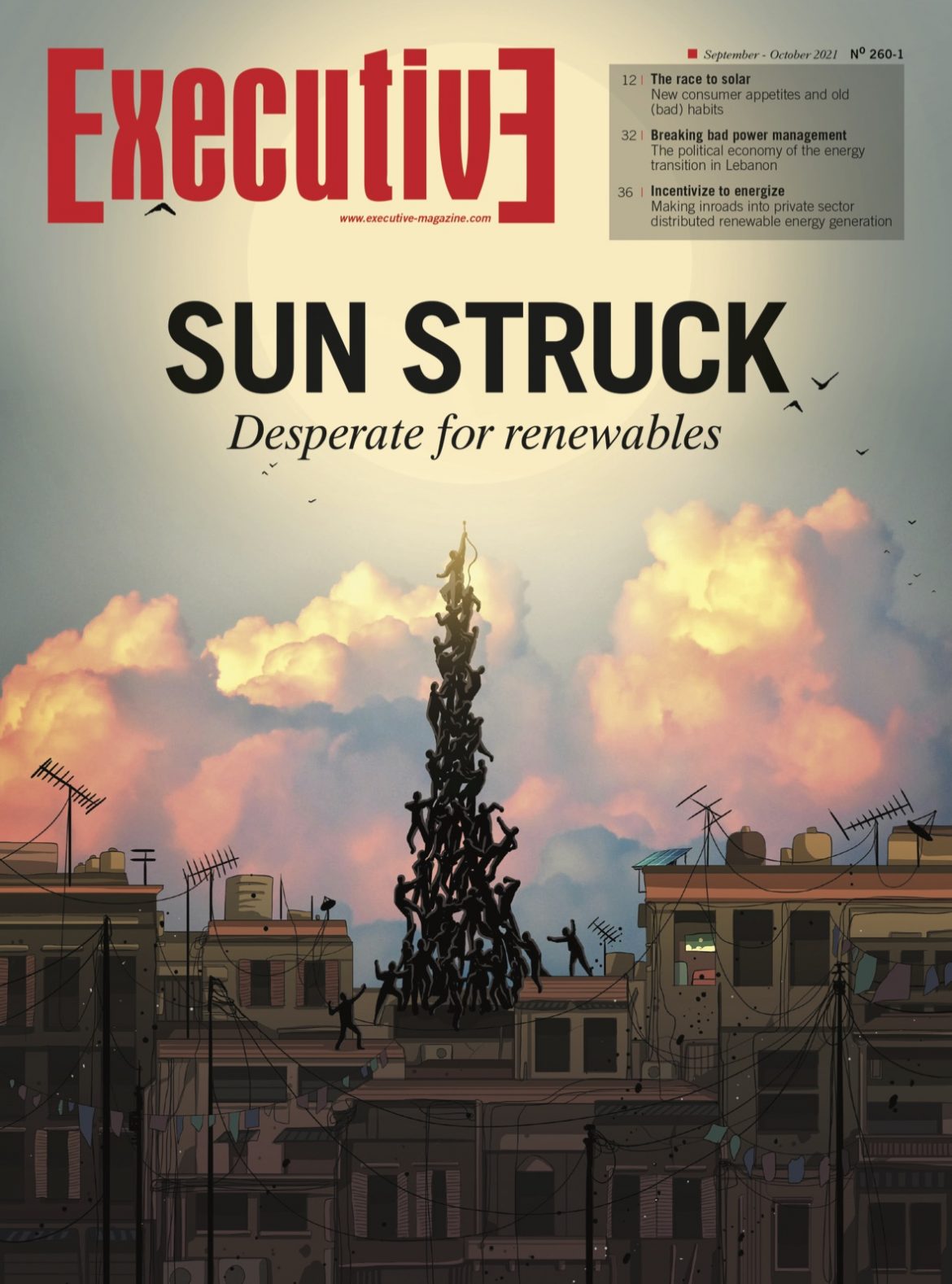

Dangling hopes for alternatives

Nothing illustrates the state of renewable energy in Lebanon better than the solar panels dangling on the wall of the second floor of the building adjacent to Executive’s offices. Four randomly fixed solar panels on the facade constitute the latest addition to an already cluttered scene filled with ill-arranged electricity wires, loose TV cables, dripping air conditioning split units, water tanks, satellite dishes, and unevenly clustered balconies. Each represents the individualism of the vulnerable which feeds on desperation and leads to random asynchronous behavior, and opportunity losses that can never be recovered.

The obvious comparable parallel is the electricity generator business situation. An industry that mushroomed, feeding on citizens’ hunger for a missing living essential and exploited by greed, fraud, and chaos. Absence of regulatory oversight is the ideal environment for shady, corrupt, and irresponsible practices at the expense of helpless citizens who are predisposed to adopt short-term solutions.

It is this virtue at the heart of our survival instinct that is our worst enemy. We have become masters in dealing with catastrophes, relying only on our collective yet individualist problem-solving knacks which seem to have subdued our power to stand up for what is right and confront those responsible. How many more of our rights are we willing to surrender before we realize that our escapist voyeur attitude is what is allowing our corrupt and inept political class to keep coming for more?

To Executive’s neighbor and proud owner of the new solar panels, mabrouk for now, but never forget why you had to invest in this system, and hopefully never forgive those who drove you to do so.