On any given day, a scour of Middle East business news reveals that private equity in the region is ‘hot’, owing to favorable conditions at the macroeconomic level or data on fundraising and investment, which seem to be getting bigger. Watchers of the asset class meticulously track which funds are looking for which companies and which opportunities and sectors are attracting the most private equity. The asset class’ behemoths and large-sized deals in infrastructure and other industries dominate headlines. On the surface, the coverage of the asset class looks healthy.

However, the component of private equity which is less covered than capital raised and investments is the arm of the asset class which offers the best indicator of performance, the exit. Without appropriate exit data, it has been difficult to see what trend is following the explosive growth in the other sub-data available on private equity, beckoning the question: whither to the exits in Middle Eastern private equity?

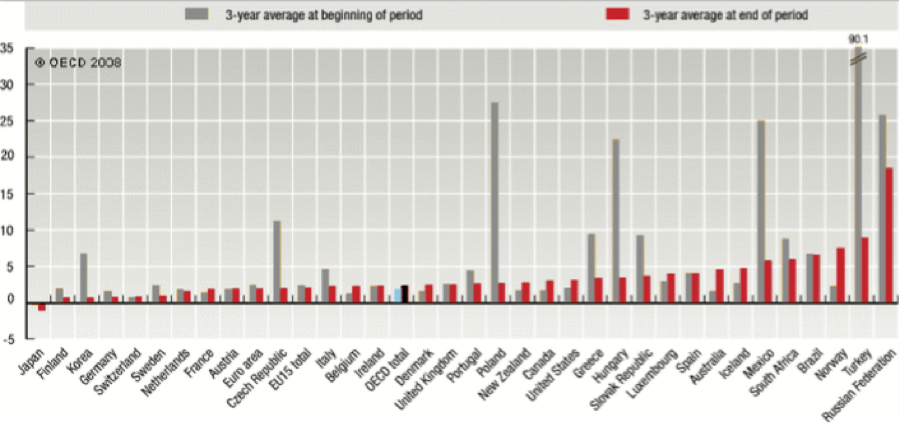

A dearth of evidence continues to pervade estimates, but some figures have indicated that only 5-10% of private equity deals in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region have been exited. With private equity comprising 45% of aggregate investment in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and 35% in Saudi Arabia, the relation between money invested and return on investment can indicate several things that a purely deal-side analysis cannot, including the asset class’ performance, potential pitfalls, and lagged performance to see if larger funds are or are not commensurate with larger internal rates of return (IRRs), the derivate used in calculating the success of funds, with ranges at 15-20% on the lower end and up to 100% in more lucrative examples. Because of some poor performance in regional bourses, private equity houses seem to be holding investments for a bit longer, waiting for appropriate exit options. With funds raised, investments complete and deals outstanding, limited partners (LPs) are going to starting demanding a return on their investment within the appropriate bounds of the fund timelines.

M&A doesn’t count

Distinct merger and acquisition (M&A) activity lies on a separate sheet from pure private equity. In M&A, a buyer bids and acquires firms to enlarge businesses both horizontal and vertically. In the case of horizontal M&A, a firm might be a competitor, but vertically, the acquired firm is a complementary entity. In the instance of a horizontal M&A transaction, a hotel chain might acquire a competitor to enlarge business or grow operations in new markets, be they different countries or a higher or lower-end of the business. In a vertical M&A transaction, the hotel chain might purchase a food services group to bring more of the hotel’s daily operations in-house. The M&A as a distinct transaction differs from the bread and butter type of private equity transaction where firms are first acquired and later exited rather than incorporated as part of a firm’s main business lines.

What then do the longer partnerships between private equity players and firms indicate? There are several speculative guesses, including the disparity in vision which could entangle maneuvering by management, making a firm reluctant to realize an exit. Another possibility is the poor exit environment, while still another is the possibility that private equity funds backed by institutional investors such as sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are bound to the wishes of these LPs and blurring the pure business thought of profit and yielding to the ‘what’s best’ scenario for firms under management.

Trade sales

Some private equity exits have come in the form of the trade sale. This type of exit is viable for the region’s numerous family-owned firms, who would like to retain control after beefing-up the best practices instilled by a private equity firm. In June, 2008 the Foursan Group exited the Abdali District in Jordan to new investors via a trade sale, while Abraaj Capital exited both EFG-Hermes and the Maktoob Group via this route in 2007. Additionally, Injazat Capital exited its stake in Atos Origin Middle East, through a trade sale exit for the GCC-based technology firm.

Secondaries

The secondary market has given a new dimension to the private equity business. It is heralded as a way to unload a firm to another private equity player and will doubtlessly be used while more traditional exits like the initial public offering (IPO) route remain weak. The largest secondary transaction was Citadel Capital’s exit of Egyptian Fertilizers Company in June 2007 and while others have not been reported as secondary sales, the private equity to private equity nature of an investment is one way of gauging the exit type.

Strategic sales

The strategic sale of a firm to a related firm covering the same or similar industries is another possibility for MENA firms and might be the destination of most unreported or disguised exits. In June, the Foursan Group exited Arab Orient Insurance Co., a Jordanian insurance provider, to Fairfax Holdings, an insurance group looking to beef up the scope of its services.

Fairfax Holdings is a Western firm that acquired Arab Orient Insurance Co. for one possible reason: to expand Fairfax Holdings reach into a new market in the MENA region. With an ever growing population consuming ever more goods, firms servicing large markets with great potential will attract the likes of more Western firms looking to establish an arm in the region.

IPOs

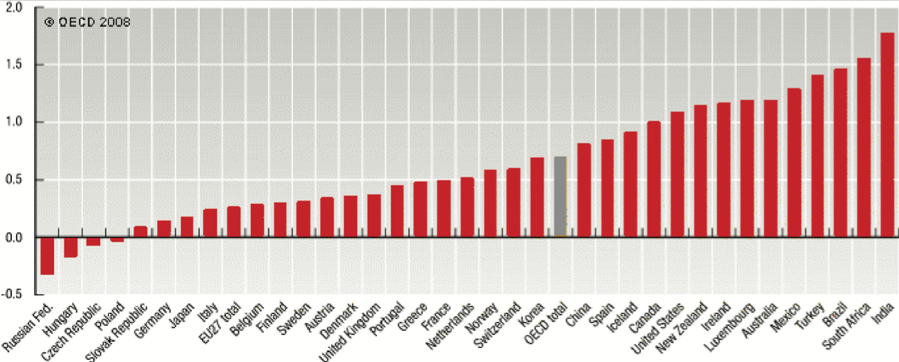

The most traditional of exit options for private equity firms — the IPO — has not be used by firms reticent to face the valuation of a firm in the open market. According to Private Equity International’s survey, 33% believe that valuation and control are the greatest threats to the growth and development of the private equity industry in the Middle East while 25% believe it is non-initial public offering exits. In 2007, securities markets in the MENA region mimicked the situation globally and reported fewer groups in 2007 than year to 2006, when the turmoil on capital markets began. Although Q1 2008 performance remained poor, the situation as a whole for 2008 remains positive. For instance, the Saudi Arabian stock exchange has grown from a low in July 2007 to remain up over 25%. Regional bourses have followed similar trends.

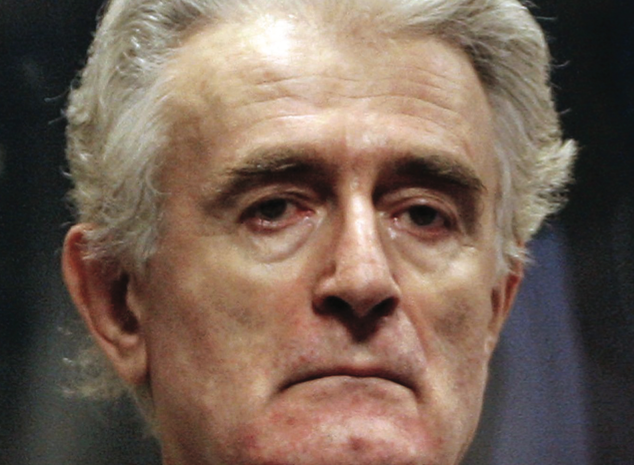

However, a less sanguine conclusion is drawn vis- à-vis regional inflation rates, which can deteriorate investments and the value of companies choosing to list restructured operations now. In an approximated situation where capital market indices are achieving 20% annual growth in capitalization figures, double digit inflation can prick the balloon of optimism.

Large time horizons

With private equity firms tabling the immediate or traditional exit, the business is taking on longer time horizons for investments. The asset class’ main driver in the MENA region is currently infrastructure, which, by the nature of the industry, involves longer holding periods between investment and exit.

Initially evoked to describe pipes, roads, and ports, the term ‘infrastructure’ has come to include a myriad of sub-industries, including downstream industries and suppliers as well as networks involved in social infrastructure, namely the hospitals and schools being built to care for the populations of new cities and the growth dynamics associated with large Arab families.

Tertiary educational institutions, from new universities to research centers, are additionally accommodating the jobs to be demanded when the under-18-year-olds turn of age. For 51% of those surveyed by Private Equity International, infrastructure will attract the most investment interest in the next twelve months, followed by energy in a distant second at 20%. The two industries involve longer time horizons owing to the scale of deals as well as the timeline to realize results.

Private equity fits into the equation by its ability to recapitalize the infrastructure industry. Statistics have accounted for infrastructure projects comprising over 60% of new funds raised by regional private equity firms. New funds are sprouting up to bolster the demand. Al Khayyat, Rasmala, and RHT recently acquired a 13% stake of Taaleem, an educational specialist, which increased Al Khayyat’s stake in the firm to 25%. Taaleem is not the only education firm seeking or gaining capital to finance growth plans. Online educational resources, private educational institutions, books, and universities have all benefited from seeking out private equity growth capital, especially as many are battling for regional supremacy, moving beyond conquering just Riyadh and Jeddah to include operations in Abu Dhabi, Kuwait City, and Manama.

With longer holding periods and new industries in which private equity players are investing, the asset class has taken on a flavor distinct to the region. Two reasons come in play to understand this dynamic. The first includes the aforementioned style of partnership in the region, with LPs consisting of SWFs in addition to individual fund backers. Sovereign wealth does not expect the same returns on investment and deals can be political to an extent in that GCC SWFs partner with MENA-centric private equity houses to strengthen the business climate in the region. An additional factor less thought of is the need for strong financial services houses. Because private equity is the quintessentially efficient type of investment, the savoir faire of industry experts is useful in structuring the longer-term outlook of firms involved in infrastructure or energy.