Teeing off at the Royal Springs Golf Club in Srinagar, Kashmir, it was not hard to see what would attract Arab golf enthusiasts looking for a slightly more adventurous destination.

The mountainous backdrop, the trees in autumnal reds and oranges, Dal Lake behind, and a course designed by golf architect great Robert Trent Jones, all make the club the best in India.

But the problem at the club is the lack of players, and that is not due to the exceedingly low green fees ($20), club hire ($5) or caddie service ($2). It is “because of the situation” said manager Rafiq Azad, sounding not unlike a Lebanese businessman.

Azad was referring to Jammu and Kashmir’s 60-year struggle for independence, and the militants — largely Pakistani-backed but now dwindling in number and popularity — that have waged a 20-year insurgency against the Indian state.

The ongoing situation in Kashmir has destroyed lives, acted as a catalyst for emigration, generated tensions between Delhi and Islamabad, and is costing the Indian state some $7 million a day to station one million troops there.

This is all the more tragic as Kashmir was once a popular tourist destination, famed for its mountains, lakes, flowers and skiing, and called locally the “second Switzerland” — all comparable to that so-called “Switzerland of the Middle East,” Lebanon.

Azad said he wants to attract Gulf Arabs to play at the club, but until there is more investment, an international airport opens, and people feel it is safe to go to Kashmir again, this northern part of India will remain wanting. Even from Indian investment.

The big money is being made elsewhere in the world’s second largest growing economy, just as it is by Lebanon’s (and indeed, the Levant’s) cousins in the Gulf. That is where the Indian-Arab relationship is blossoming, in recent decades rekindling an ancient mercantile relationship, with India signing bilateral protection agreements with nearly all the GCC countries.

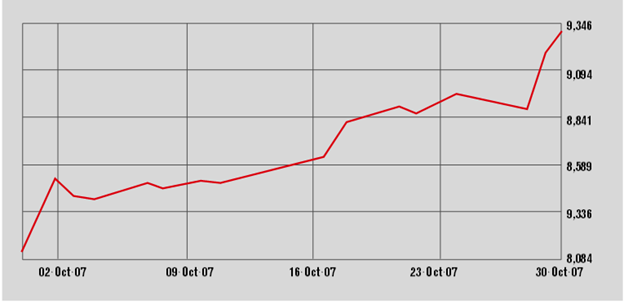

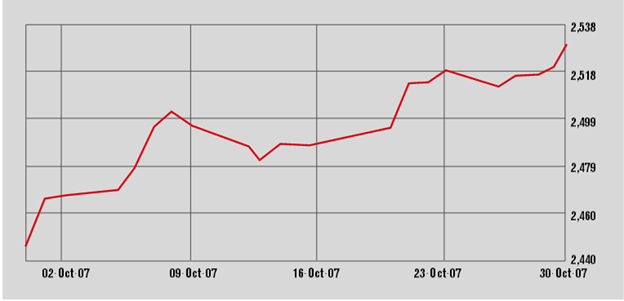

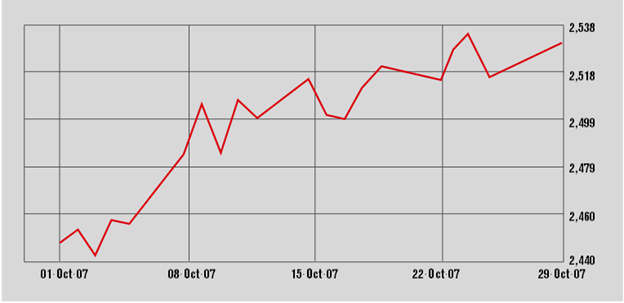

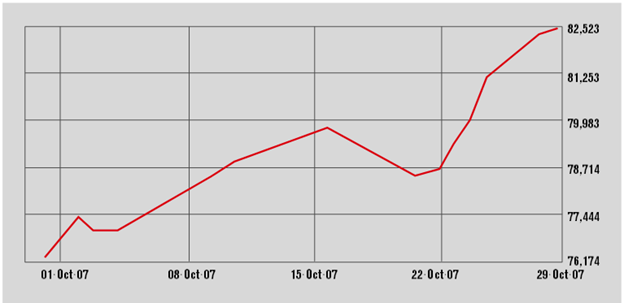

As India’s economy is growing at over 9% a year, it is not surprising Indian exports to the GCC are surging, up 17% from 2005’s $14 billion to $16.7 billion last year. And if India signs a FTA with the GCC, two-way trade could reach $40 billion by 2010.

With such a booming economy, India’s 50 million middle class have increasingly more rupees in their pockets, a demographic that Lebanese luxury retailer Aishti is rumored to be wanting to move in on, and Dubai’s Emaar already has.

The economic outlook is apparently bullish, with the middle class expected to surge to 40% of the population, to 587 million, by 2025, according to a McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) study, due in part to a growing 16-64 years old age range, from 700 million in 2005 to 950 million in 2025, and household income tripling in the next two decades to bring India up from the 12th largest consumer economy globally to fifth position.

This may come to be, but a lot will have to change to alter recent government statistics that state that 92% of the population are informal workers, and some 836 million (77%) of Indians live on less than 20 rupees ($0.50) a day. As for the 10 million Kashmiris in India, a viable solution to the situation is needed between Delhi, Islamabad, and Beijing (which controls 10% of Kashmir), as well as divisions among the Kashmiris — a bit like Lebanon’s situation with all and sunder poking their noses in. Indeed, Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi influence has spread to Kashmir, there is widespread support for Iran (and Hassan Nasrallah) among the 20% of the population that are Shia, and Israel is reportedly seeking to gain a foothold as well, according to academics at Kashmir University.

But as this is the festive season, let’s be optimistic. The McKinsey’s figures might not be pie-in-the-sky forecasts and political and economic realities can be overcome. All Indians will get a slice of the economic pie, Kashmiri golf clubs will have membership waiting lists, and peace will come to all men in the troubled North India region and the beleaguered Middle East.

It might also be worth my teeing off from Beirut’s golf course as an act of solidarity, but perhaps in the new year, regardless of the “situation.”