A hard look at Lebanon through an economist’s lens would reveal that the national outlook is dismal, the damages accrued during the latest war are staggering, and the political future of the country is fragile and indeterminate. Thankfully, there are plenty of other lenses through which to view a country and its people, and these various angles can illuminate even economic truths that may be overlooked by global economic assessors such as the World Bank or International Monetary Fund. If economics can be boiled down to people’s behavior around material wealth, production, and consumption, Lebanon shows high levels of strength and a remarkable capacity for collective economic support.

Amid the devastation wrought by the past year of war, Lebanon has demonstrated—once again, as after the Beirut blast and in other periods of catastrophe—its singular capacity for a nearly nation-wide mustering of support and show of solidarity. Despite facing relentless attacks on its infrastructure, the country’s citizens, organizations, and private and public sector institutions mobilized to address the escalating crisis in a collective humanitarian response.

Lebanese healthcare workers have continued their lifesaving efforts despite being under direct threat. Hospitals and clinics have been targeted in multiple airstrikes, forcing medical staff to operate in perilous conditions. Field hospitals have been established in makeshift locations to ensure emergency care reaches the injured, even in areas where former medical facilities have been destroyed.

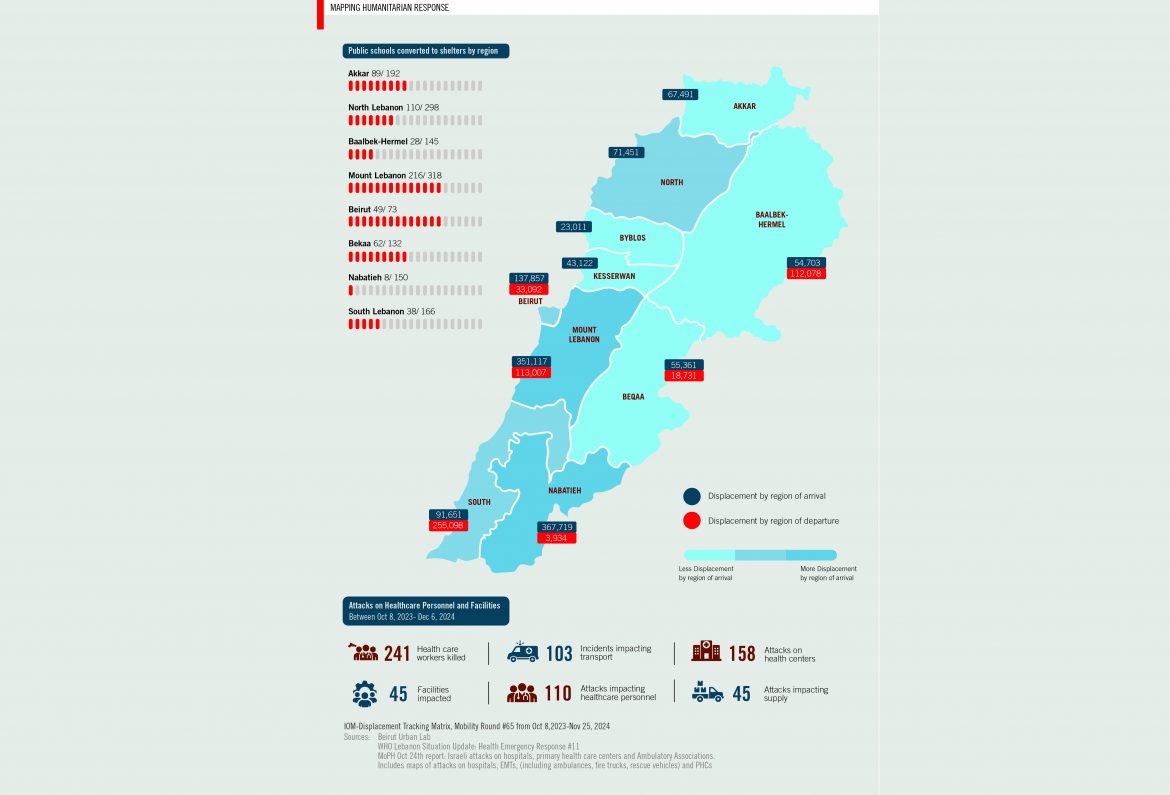

Ambulance crews and first responders have risked their lives to rescue civilians trapped under the rubble, often venturing into areas still under attack while knowing that medical personnel and facilities became deliberate targets during the war. Reports detail instances of paramedics working without pause despite the bombing of ambulances, medical centers, and civil defense centers. The Lebanese Red Cross and other humanitarian organizations, of diverse secular, religious, and sectarian backgrounds, have played a critical role, coordinating these rescue missions and providing essential medical supplies amid shortages. In total, at least 241 medical workers were killed while on duty during the conflict.

Lebanon’s food aid response has been prodigious, with local organizations, municipalities, and international aid groups mobilizing to deliver over 50,000 tons of food supplies to displaced families, as reported by the Lebanese Food Bank in December 2024. According to Caritas Lebanon, a Catholic aid organization, volunteer-run kitchens in Beirut, Sidon and Tripoli prepared 20,000 meals on a daily basis for displaced families. The scale of both the need and the response has been so immense that figures are difficult to quantify. In the private sector, local farmers and industry operators have contributed to nationwide efforts and created networks of support and resource-sharing platforms, pooling and lending resources to ensure basic needs are met and to keep economic activity afloat.

With upwards of a million people displaced during the height of the conflict, Lebanon transformed around 1200 of its public schools into shelters to provide immediate refuge, turning classrooms, playgrounds and public halls into havens from violence. According to UNHCR, shelters in Beirut alone housed over 10,000 people, with churches and mosques opening their doors and serving as focal points for aid distribution. Many local NGOs appealed to the Lebanese diaspora for donations, and in some cases, Lebanese expats organized fundraising channels.

Lebanon’s strong interdependent network of formal organizations and informal familial or community structures that serve as a safety net in lieu of public sector support does not factor into economic assessments conducted by organizations such as the World Bank. It is, however, Lebanon’s surprisingly sturdy lifeboat that steers the country through repeated storms. But lifeboats, however dependable, are not meant to do all the heavy lifting; it is imperative that Lebanon get its proverbial ship in order if the country is to have any chance at making it through future storms alive.

![Mireille Korab Abi Nasr FFA[1]](https://www.executive-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Mireille-Korab-Abi-Nasr-FFA1-scaled-e1734340299386-1170x681.jpg)