Amid plots of unsold, multi-million dollar reclaimed land, on what was 30 years ago an uncontrolled garbage mountain rising from the sea, Downtown Beirut now features more completed buildings than cranes. However, the Beirut Central District (BCD) has been hit hard by stagnation in the real estate market that began in 2011. While projects launched at the beginning of the decade have been delivered or are nearing completion, sales ratios mean investors have still not realized gains.

Solidere, the company created by Parliament in 1991 and founded in 1994 to oversee rebuilding of the BCD, in the past handily published project updates throughout Downtown in its annual report, but the company’s most recently published review of yearly performance on its website is from 2014. Interviews and desk research, however, confirm that three residential towers on the western flank of the BCD were delivered in 2017: Beirut Terraces, the DAMAC Tower, and 3 Beirut, all launched in 2010. Other large-scale projects—such as the GC Towers south of the Martyrs’ Square statue, first announced in 2008, and District S, launched in 2010—are still at least 12 months from completion. The very ambitious Phoenician Village never broke ground, while the fates of the Landmark mixed-use project at the foot of the Grand Serail and Beb Beirut residential tower, just north of the ring-road on the Martyrs’ Square axis, are unclear. Meanwhile, Beirut Gardens—between Rafik Hariri’s burial site and the Virgin Megastore—looks closer and closer to completion, even as one contractor on the project still advertises a 2014 delivery date on its website.

But even as construction continues, the pace of sales for developers who bet big on BCD is still struggling to keep up.

The good ol’ days

Since 2011, developers operating in the central district have struggled to attract clients to buy their properties. But times were not always so difficult. Following the summer 2006 war, Lebanon experienced an economic boom, and pent-up demand drove construction activity to heights not seen since the 1990s. From 2007 until 2010, developers built as quickly as possible, targeting the expensive tastes of Lebanese expatriates and foreign clients, based mainly in the Gulf.

“When the boom started in 2007, 2008, and extended until 2010, almost all of the supply was life-sized, luxury apartments because it was targeting the expatriates,” recalls Nassib Ghobril, chief economist at Byblos Bank. “People here, the developers, thought that every expatriate was a multi-millionaire that had a briefcase full of cash to throw at real estate. That’s what they saw. They built 400, 500, 600 square-meter apartments.”

Amid seemingly insatiable demand, a profusion of amateur developers entered the market, inflating the availability of housing in Lebanon. Speculators chased after these residential offerings, encouraging even more construction. Carlos Chad, managing director of Demco Properties says that a lack of professionalism and due-diligence during this period led to problems in the market later on. “There was an oversupply that was mainly due to the fact that a lot of pseudo-developers went, built buildings, and proposed a lot of units without making any [kind of] market study. [They] didn’t [investigate] the market to understand what was the real need, what was the purchase power, what were the budgets, what were the sizes,” explains Chad.

[pullquote]Clients from the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) were some of the first to lose their investment appetites[/pullquote]

The good times proved to be short-lived. Clients from the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) were some of the first to lose their investment appetites. Nimr Cortas, a co-founder of Estates, says that he noticed a downturn in foreign acquisitions as early as 2009 when oil prices fell, impacting wages in the Gulf. This coincided with tension in the relations between Lebanon and the GCC over Iranian influence in the country, which alienated even more non-Lebanese clients.

Then, in 2011, uprisings throughout the Middle East eventually took root in Syria, pushing the Lebanese economy into a uniquely long period of economic stagnation. Wary of the investment climate in Lebanon, expatriates curbed their purchases in the country. This put many of the developers in the BCD area in a bind. Previously, development companies tended to acquire land with liquid capital and then finance the construction of their products with presale revenues. When turnover slowed down developers had to find alternative methods of paying for the completion of their projects. As a result of the crunch on liquidity very few new buildings have been initiated within Downtown, and progress on projects launched before 2011 has been slow, with developments taking five or more years to complete.

Thousands of unsold units

The legacy of the boom years today is an overabundance of luxury residences in the downtown area, often with a price tag over a million dollars. Ramco Real Estate Advisors estimates that there are now 3,600 unsold apartments in the BCD alone. The excess supply has forced property owners to reduce their margins and offer discounts of 20 to 40 percent in order to move their inventory.

In recent years, several large buildings have been delivered and others are near completion in the downtown area. Most projects of this generation were started just before 2011 and were therefore able to capitalize on the final months of the boom period. The timing meant developers could collect presale revenues that helped make the projects economically viable. Still, these purchases were generally well below the approximate 60 to 70 percent sales ratio that is required before developers begin to turn a profit on their investments.

The case of the luxurious GC Towers, near the Mohammad Al Amin mosque, aptly demonstrates the difference a few years time can make. When the project was launched in 2009, Ghada El Khatib, COO of Plus Holding, reports that 40 to 50 percent of the apartments—between 6,000 and 10,000 square meters—were quickly bought up. However, the discovery of ancient ruins on the site required that construction be halted until the Department of Antiquities secured the artifacts on the ground. By the time the project was resumed years later, the market had turned and many investors pulled out. “We have sales yes, but not like [before 2011] because of the stopping of the project. If the project didn’t stop, we could have been sold now 100 percent.”

Eying delivery dates one and two years down the road, Khatib says that the towers still have a long way to go before they begin to generate profits as only 55 and 60 percent respectively have been bought up. “We have to continue what we have started, even if we have a shortage of money. We need to deliver because there are many people who need to be given their apartments. It’s not about revenues, it’s about credibility.”

Several recently completed developments in the BCD area managed to sell out completely prior to 2011, according to Mohamad Sinno, managing director of Vertica Realty Group that consults with companies operating in Downtown—including the Platinum, Marina Towers, and Karagulla buildings. Benchmark’s Beirut Terraces and 3Beirut by SV Properties and Construction, are currently being handed over to clients and are believed to have sales ratios of between 50 and 70 percent.

Where are the people?

As for occupancy rates, Carlos Chad, says many developers are moving into office construction to diversify their portfolios and hedge against stagnation in the residential market. “In Solidere it happened a lot because there was an oversupply, and the other problem was that Solidere was becoming a ghost city because a of lack of investors, the locals couldn’t afford it, only the expats could afford it. The wealthy expats who come once or twice a year. So you have 50 weeks of vacancy, so it’s a dead city.”

While much of Solidere’s Downtown sits uninhabited, property taxes and service fees eat away at developers’ revenues. In 2017, Sinno noted that a number of new service companies are making their way into the downtown market and are helping reduce the cost burden on vacant units. “Before, it was a monopoly in Solidere. Now you see new players coming into the market, which means competition, which [also] means better prices. So it’s changing a bit,” says Sinno.

On the whole, both developers and consumers have grown increasingly indebted to banks since 2011 through building and purchasing accommodations. “Their [banks’] exposure to the sector has increased during the previous years, and if you measure it by, say housing loans plus construction loans, their exposure to the real estate is about 40 percent of the whole credits to the private sector,” according to Marwan Mikhael, head of research at Blom Bank.

A controversial solution

In an attempt to house some of the real estate sector’s non-performing assets Estates’, Cortas, along with colleague Massaad Fares, are attempting to launch a billion-dollar investment fund. Intending to make use of a 2016 central bank circular, they hope to attract enough capital to launch the fund within a couple months.

Yet many economists remain skeptical about the feasibility of the fund and its implications for the real estate market. “These are not distressed properties simply because they are vacant, and there is no demand for them,” says Ghobril. “[It] is distortive to the market, in my opinion. What prices will they pay? How much will they have leverage over the developer? How will that affect other segments of the residential real estate? And the other question is: Are they going to be able to raise one billion dollars?”

With or without the fund, much of the BCD will remain as it is today: abandoned. For most Lebanese who cannot afford to live in the area, the downtown lost its only appeal in 2015 when garbage protests and the ensuing security crackdown led to the closure of bars and businesses along Uruguay street and in Place de L’Etoile. Despite the modern structures, high-end retail, and luxurious apartments, a nighttime stroll through the area shows that, while the Downtown may have been built, the lights still are not on.

Going into 2017, real estate stakeholders were riding a wave of optimism spurred by the end of a nearly three-year presidential vacuum and the formation of a unity government. After several years of market stagnation, developers willed themselves to believe that consumer confidence would be restored and residency uptake would finally resume. Buyers were also hopeful that political stability could improve the economy and enhance the investment climate. Yet the enthusiasm proved to be a setup for collective letdown as 2017 quickly became another disappointing year for the real estate sector.

Shortly after the appointment of a cabinet, Parliament turned its attention to increasing both public sector salaries and state revenues via the imposition of new or increased taxes and fees. A number of these fiscal measures targeted the real estate sector, increasing the price of each ton of cement and applying a 15 percent capital gains tax on secondary residences. For developers who were already struggling to maintain profit margins amid an economic downturn, the timing could not have been worse.

“We were really optimistic about 2017 because we had a president … [and] we have a new law for elections, plus we felt there was potential in the last quarter of 2016. So this is why we wanted to finish our [projects] in order to prepare for 2017,” says Ghada el Khatib, COO of Plus Holding. “Unfortunately, the government doesn’t help in any sector … You know it’s like they act like our enemy, not our supporters,” she explains, referring to the new tax regime.

According to the Byblos Bank/AUB Consumer Confidence Index, end users in Lebanon are feeling more positive overall compared to the monthly average in 2016, although the sentiment has not been sufficient to substantially boost sales amid consumers’ high expectations for 2017. Throughout the year, the tax law persistently weighed on consumer appetites. Parliament’s discussion of the law alone caused confidence to decline four months in a row from January to April. The largest drop was noted in July when the index tumbled 13 percent after the tax law was passed.

Rush to register

While Executive was unable to compare this year’s sales transactions figures from the Central Administration for Statistics (CAS) to its existing data set (as the numbers have yet to be released), statistics from the General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre (LRC) appear at first glance to contradict the dismay expressed by industry professionals. According to LRC figures cited in a report by Bank Audi, there was a 15 percent year-on-year increase in real estate transactions from January to July.

It is doubtful that the number of transactions is actually reflective of a significant recovery in market activity, however. Transactions are tallied using property registrations, and buyers in Lebanon are able to defer these registrations for several years. An official at the LRC explained that many buyers were pushed to register their properties in 2017 due to a rumor that the government would hike registration fees, thus accounting for the uptick that otherwise suggested a sales surge no developer has reported.

Although the fee-hike rumor proved to be false, it was based on a real change in the registration process. Following the implementation of the new tax law, buyers can no longer delay paying the entirety of their registration fee by holding off on registering the purchase. The new law says buyers must pay 2 percent of their asset’s value immediately, regardless of when they register it. This misunderstanding likely caused a surge of registrations for properties that were acquired in previous years before title deeds were turned over.

[pullquote]We were really optimistic about 2017 because we had a president[/pullquote]

With the exception of sales transactions figures, most real estate sector indicators showed little change. When changes were identified, they often reflected a downward trend. For example, cement deliveries fell by 105,626 tons to 3,787,589 from January to September of this year compared to the same period of 2016. This may point to reduced building activity, although cement production operates somewhat independently of the real estate sector and includes infrastructure projects, as well as exports.

More telling is the decline in the number of issued construction permits as compiled and published by Banque du Liban (BDL), Lebanon’s Central Bank, which decreased 5.4 percent to just over 10,000 in the first nine months of 2017, compared to the same period in 2016. The total area covered by construction permits was also down by 3.2 percent in the first nine months of 2017, compared to the same period in 2016, putting the total decline of permit area at 31 percent since 2011. As real estate projects that broke ground nearly 10 years ago finish up around the country, developers are finding it harder to finance new developments under the strain of dwindling liquidity. According to Karim Makarem, director of RAMCO Real Estate Advisors, challenging market conditions are even inhibiting the sale of land.

“The newest trend is that developers are not buying land in 2017. There are very few developers out there looking to build new projects. I suppose that’s an important thing to say, whereas in the past you’ve always had some developers out there in the marketplace looking to identify lands for development. Now, not all, but most of those looking to buy land are investors looking to buy discounted land,” he says.

Advantage: buyer

Since 2011, local buyers in need of new housing were fueling demand. For these prospective buyers, budget tends to be the determining factor in their acquisitions. Indeed, Bank Audi noted a “flurry of apartments/studios below 150 square meters” coming onto the market in 2017, representing a strategic pivot to smaller units that developers made when the slump started.

“There hasn’t been much change in the dynamics of the residential real estate sector in Lebanon in 2017,” explains Nassib Ghobril, chief economist at Byblos Bank. “The sector, generally speaking, is still stagnating. The only active segment of that sector is the small-size apartments, 150 square meters and below, and the demand is coming from people who qualified for the Public Housing Corporation [subsidized] mortgage package. That’s about it. Basically that’s what’s driving demand for residential real estate in the country.”

[pullquote]Developers are finding it harder to finance new developments under the strain of dwindling liquidity[/pullquote]

And while official asking prices for residential property have hardly budged since 2011, RAMCO, which tracks the price of developments in municipal Beirut for projects starting at $3,000 per sqm on the first floor, calculated a drop of only 1.7 percent in 2016 with a similar decrease of under 2 percent expected in 2017. In reality, developers are being forced to offer large discounts in order to sell their stock.

Marwan Mikhael, head of research at Blom Bank, explains, “Starting with the downturn in 2012 until now you will have a decline in prices depending on where you stand. For me, the market, you have to divide it into the luxury market, the middle market, and the low market. In the luxury market, you have a decline of 30 to 40 percent in price since 2012 until now. In the middle you have between 15 and 25 percent decline, and on the low side, you have 10 to 15 percent.”

Shifting strategies

Amid low consumer confidence and a growing quantity of housing at ever cheaper rates, prospective buyers are not in any rush to make housing purchases. In response, developers are experimenting with a range of coping strategies to survive this period of economic stagnation. Mohamad Sinno, managing director of the real estate consultancy Vertica Realty Group, says that one of his clients has introduced a lease-to-own arrangement at the Beirut Terraces. Demco Properties is also considering a similar option whereby renters would pay 5 percent of the apartment’s value to put a hold on the residence for a rental period of up to three years. Later, if the tenant decides to purchase the unit, 50 percent of the accumulated rent would be deducted from the final sales price. This arrangement could help developers attract buyers without the negotiation of hefty discounts that cut into their margins.

Other companies are putting their hopes in other markets altogether. Khatib says that Plus Holding is looking to finish its current projects as soon as possible while expanding outside of Lebanon. “We are trying to get new markets, like in Cyprus and Greece. We are mushrooming outside the country because Lebanon for us is our country, we have to keep a good reputation, a good quality, a good service. But is it a profitable country? No it’s not, unfortunately,” laments Khatib. “Do you want to invest more in this country for the time being? No.”

The government is also attempting to stimulate investment in the sector through an initiative by BDL, in conjunction with the ministry of foreign affairs. Together, these institutions are reaching out to Lebanese expatriates with high purchasing power by introducing a housing loan tailored specifically to them. The so-called expat mortgage allows Lebanese residing outside the country to borrow at a 2 percent fixed rate for up to 30 years.

For now, it is too early to tell how impactful the expat mortgage could be. Subsidized housing loans for resident, first-time homebuyers enabled by BDL have been keeping the sector afloat since 2012. Ghobril notes that the value of mortgages has nearly tripled since 2010, from $4.5 billion to $12 billion at the end of 2016. In 2017, the number of outstanding mortgages is thought to be around 125,000.

Fourth quarter lending may be diminished due to confusion surrounding the disbursement of the central bank’s subsidies. Several economists and industry stakeholders interviewed by Executive said the central bank had instructed commercial banks to suspend lending at subsidized rates until early 2018. This was said to be due to the central bank maxing out its budget for subsidies early in the year. An official at the central bank contradicted this notion, asserting that all subsidized mortgages were frozen for two weeks starting on October 5. On October 20, the Public Housing Corporation reintroduced its loan at a 3.6 to 3.8 percent interest rate. The expat mortgage, and another loan subsidizing office space for SMEs, were switched from lira to dollars. According to the official, all other subsidized mortgages are currently being approved.

For the most part, developers are ready to put 2017 behind them, while trying to remain optimistic about a Doha Accord-style u-turn in the upcoming year. However, industry professionals acknowledge that the surprise resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri stalled what little momentum had been achieved prior to November. With political jostling still unresolved, the light at the end of the tunnel remains a distant dream for Lebanon’s real estate sector.

Banking & finance

[media-credit name=”Ahmad Barclay & Thomas Schellen” align=”alignright” width=”620″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[media-credit name=”Ahmad Barclay & Thomas Schellen” align=”alignright” width=”620″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[media-credit name=”Ahmad Barclay & Thomas Schellen” align=”alignright” width=”621″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[media-credit name=”Ahmad Barclay & Thomas Schellen” align=”alignright” width=”620″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Corporate governance in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) has been insufficient and is preventing corporations from fulfilling their economic potential. Corporate governance is crucial when companies seek to attract new shareholders and optimally mobilize sources of capital, but publicly traded companies in the region are not only lagging behind developed economies in terms of corporate governance, but also behind many emerging markets.

Transformations of corporate management culture have recently commanded a great deal of attention in international business literature. One particular focus is the optimization of corporate boards through the increased inclusion of female board members.

It is in the area of female participation in corporate governance, so on the board of directors, that companies in the MENA region face particular shortfalls, which has unfavorable implications on corporate governance culture throughout the region. Globally, women account for only 12 percent of board seats among the world’s largest companies, and 13.4 percent of directors in developed markets, versus 8.8 percent in emerging markets, according to data from MSCI, a global equity indices compiler. But despite this low target, in the Middle East, fewer than 2 percent of board members are women, according to Bloomberg figures.

If a correlation between the low adoption of corporate governance and low rates of women on boards is drawn, corporations in the MENA have the opportunity to kill two birds with one stone by simultaneously improving their corporate governance practices and establishing policies to increase the number of women serving on boards. There are sound reasons to do both, for corporate culture and overall performance alike.

Family business

A primary reason for the slow pace of corporate governance reform in the region is that the majority of businesses are either family-owned or small- or medium-sized enterprises. These companies tend to hire from within, especially for top positions, rendering it difficult to maintain independent and transparent governance.

By definition, corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled. It hinges on how the company’s board of directors and upper management communicate with its shareholders and stakeholders.

With proper governance, any organization would be transparent and accountable for every decision it makes. This fosters a healthy and symbiotic environment. Inversely, weak corporate governance permits waste, corruption, and mismanagement due to a lack of accountability. The more transparent and forthcoming the organization is about its actions, the more amicable the relationship can be between management and shareholders.

Sound corporate governance requires supervisors who are responsible for constantly reviewing and reevaluating all of a company’s processes and regulations. In the case of any errors or mishaps, they are required to instigate proper changes that will prevent such issues in the future, and make them less harmful to overall profit and performance.

These practices should be made clear to all stakeholders, and any change needs to be promptly reported. The shareholders also hold the right to question any reforms the company implements, or new projects it undertakes, to ensure that such ventures do not have negative impacts on internal or external stakeholders.

There are many benefits for cohesive corporate governance at multiple levels. For a company, it eases access to external capital, bolstering its competitive edge. In the case of family-owned organizations, the distribution of power and capital is very clear, which lessens the possibility of conflicts erupting between family members. The latter is crucial to attract new investors and placate those who are already established. Internally, it will create a transparent feedback mechanism that will root out any weak operations that are compromising productivity.

Properly implemented and transparent corporate governance often attracts shareholders, who are more likely to invest if they have access to all the information regarding the spending of their money as well as the projected success. Furthermore, sound governance will encourage present shareholders to support further expansion into new projects and products that will develop the company and help it remain competitive. This cannot be achieved unless the shareholders are being routinely updated with all the latest findings and regulations that are implemented.

Numerous empirical studies have shown that investors are significantly more likely to invest in a well-run organization than in a poorly-run one. The corporate value of any organization will be bolstered and subsequently add value to the economic status of the nation.

Including women on corporate boards is a crucial way to improve corporate governance. Studies by international accountancy groups Deloitte and EY have shown that investors and shareholders increasingly see the value of gender balance in businesses, and that shareholders care about the gender composition of boards.

Women on boards

Importantly for the bottom line, a 2016 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report, citing McKinsey, showed that companies with women on executive committees outperformed those without women in leading positions, bringing in an average of 47 percent more return on equity and 55 percent more earnings before interest and tax.

Findings from narrow market segments—such as listed Fortune 500 companies in the United States—that show improved bottom-line performance of companies empowering women strongly across various levels of decision-making are difficult to extrapolate to international markets. However, an analysis carried out a few years ago by the Peterson Institute for International Economics on 21,980 firms in 91 countries indicated that including women on boards may improve corporate performance, “with the largest gains depending on the proportion of female executives.”

The OECD, which is championing corporate governance, has issued a recommendation on gender equality, advising that jurisdictions “encourage measures such as voluntary targets, disclosure requirements and private initiatives that enhance gender balance on boards and in senior management of listed companies, and consider the costs and benefits of other approaches such as boardroom quotas.”

Introducing quotas to get more women on boards has been proven to be effective. In France, for instance, once a quota was introduced in 2011, the share of women on boards went from 10.7 percent in 2009 to 33 percent in 2015, while there was an 18 percent increase over a similar period in Italy.

Yet despite such progress there is still a seemingly widespread belief that women are not qualified to be on boards. This argument does not hold up to reality. The number of women in higher education outstrips the number of men in Lebanon, as well as in many MENA countries, while in the Lebanese banking sector, women account for 47 percent of all employees—certainly a large enough pool of talent to draw upon. What is holding back women from being on boards is not qualifications but experience. To have that experience, women need to be able to move up the ladder and break through the glass ceiling. That requires a mindset change in corporate culture.

Among family-owned businesses especially, a dual-track approach to corporate governance and increasing female participation in management and boards in the MENA should be encouraged. As the MENA region starts taking corporate governance more seriously, governments, regulators, and institutions should seriously consider adopting the OECD “Recommendation on Gender Equality” to boost the number of women on boards.

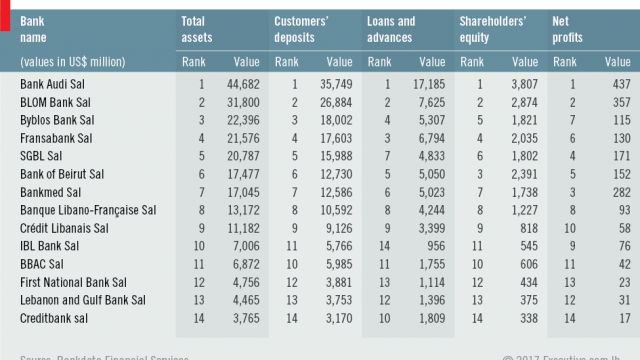

The Alpha Report by Bankdata Financial Services covers 14 banks, each of which have deposits exceeding $2 billion and collectively represent the lion’s share of banking activity—holding 87 percent of the $227 billion in assets at the end of September 2017. Before assessing the performance of Lebanese alpha banks during the first nine months of 2017, it is important to acknowledge the political climate in which they operate.

In November 2017, shortly after the Alpha Report was finalized, Lebanon reeled from the shock resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri. Much has transpired in the weeks since. Political and economic influencers universally sought to reassure the Lebanese people and their international partners that the stability of Lebanon will persist, and that its economic integrity will be preserved. The prime minister eventually made his way back home, and retracted his resignation—for now. And as the country entered into December of 2017, the commitments of key political stakeholders have seen positive developments toward stability, reinforced by the Lebanese economy’s long history of resilience and endurance.

However, given it is not yet possible to assess the impact and potential repercussions of the year-end political period, the following overview is, thus, Bankdata’s diligent view of banking conditions in the first nine months of 2017—without any speculation as to developments in the fourth quarter of 2017.

[media-credit name=”Ahmad Barclay & Thomas Schellen” align=”alignright” width=”640″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Slow but steady growth

Measured by the consolidated assets of alpha banks, banking activity saw 4.8 percent growth in the first nine months of 2017 to reach $227 billion at the end of September. In terms of human capital and presence on the ground, alpha banks expanded their networks by 14 branches and 707 persons in domestic positions in the first nine months of 2017. With these additions, the 14 banks accounted for 1,202 branches, and a total staff of 31,202 employees at the end of September. It is worth noting that the staff count of employees abroad did not increase, meaning that all additions to the alpha banks’ net employee count were domestic hires.

In continuation of long-term trends in the banking sector, activity growth was driven by customer deposits—whose growth accounted for two thirds of the asset growth in the first nine months of 2017. Customer deposits actually achieved 4 percent growth over the period; noting that alpha banks’ deposit growth was mostly tied to domestic deposits. On a consolidated basis, alpha banks’ domestic deposits rose by 4.6 percent, while foreign deposits grew by 0.7 percent year-to-date. In parallel, the consolidated loan portfolio of the alpha group grew at a slower pace when compared with previous years. As banks found the harsh economic environment restricting their lending opportunities, loan growth was reported at merely 2.6 percent over the nine-month period (compared to 4.7 percent in the first nine months of 2016).

While the bulk of deposit growth was tied to foreign currencies, almost all new loans this year were in Lebanese lira. This development, which occurred in the context of a stagnant FX loan portfolio, was contrary to what was observed last year. Domestic-loan dollarization decreased to a record low of 69.4 percent at the end of September and moved ever closer to the domestic deposit dollarization ratio of 65.4 percent at end of the third quarter. The gap between the two dollarization ratios has been contracting from 7.4 percent at the end of 2016 to 4 percent at end-September 2017. This trend has also been reflective of the impact of the financial engineering operation undertaken in 2016 by Banque du Liban (BDL), Lebanon’s central bank, that increased banks’ liquidity in local currency.

Improved returns

The growth in the alpha banks’ loan portfolio was coupled with a slight retreat in lending quality. The gross doubtful and substandard loans as a percentage of gross loans rose from 6.81 percent in December 2016 to 7.78 percent in September 2017. Net doubtful and substandard loans as a percentage of gross loans likewise rose from 2.43 percent to 3.19 percent over the same period. Nonetheless, while doubtful loans are provisioned to the extent of 71.8 percent by specific provisions, collective provisions were significantly enhanced, reaching an all-time high of 1.71 percent of net loans.

At the profitability level, alpha banks’ net profits from operating activities grew by a mere 3.4 percent over the first nine months (growth was 21.4 percent when adding profits from discontinued activities). It is important to note that the growth in recurrent profits over the first nine months of 2017 saw a real increase above the nominal growth of 3.4 percent when normalizing the profits of the corresponding 2016 period for non-recurrent fees and commissions resulting from BDL’s financial engineering operations. Nominal profit growth was driven by 2.6 percent growth in net interest income, yet offset by a 49.5 percent contraction in net fees and commission income (for the reasons mentioned above), leading to a 6.2 percent contraction in net operating income. Within the context of an 11.1 percent contraction in operating expenses, banks experienced stagnation in operating profits.

With respect to return ratios, Bankdata observed a relative improvement. While a slight increase in the return on average assets from 1.04 percent in the first nine months of 2016 to 1.19 percent in the same period of 2017 was reported, the return on average common equity rose from 12.77 percent to 14.33 percent, though still below the cost of equity of alpha banks. The components of return ratios suggest that spread has contracted by 6 BPS, moving from 1.94 percent to 1.88 percent, coupled with a decline in the ratio of non-interest income to average assets from 1.20 percent to 1.03 percent. All in all, this generated a retreat in the asset utilization rate from 3.14 percent to 2.91 percent.

The unfavorable developments were offset by a noticeable rise in net operating margin from 33.23 percent to 40.96 percent, mainly tied to the drop in credit cost from 8.00 percent to 5.76 percent, while cost to income improved from 49.70 percent to 44.89 percent over the same period. Both the asset utilization ratio, and the credit cost ratio of the corresponding 2016 period were inflated on one side by the non-recurrent revenues and on the other side by the BDL requirement for banks to use their exceptional revenues in one-time extra provisions.

Ethereal. Ephemeral. Elusive. ETP, perhaps. Questing for upcoming banking-sector development opportunities in 2018 brings a whole palette of e-words to mind, including the “e” in ETP (electronic trading platform), but not the favorite e-word of marketers and their PR minions: exciting.

It seems that development opportunities in the banking sector are increasingly scarce, partly, of course, because good opportunities are by definition those that are not obvious to all, but also because the business of banking is facing new pressures all around. Before the decade is out, 2017 and 2018 might count among years that drove this point further home.

Earlier in the 2000s, during the quasi-mythical days before the Great Recession, development logics for large Lebanese banks seemed compelling. One strong strategy calculation for a growing top bank was to go cross-border, leverage your comparative advantage of the sophistication of Lebanese financial industry knowledge in conjunction with your cultural proximity to other countries in the wider region, and deploy your accumulated financial ammunition outside of Lebanon to avoid putting pressures on the home market.

Another famed strategy for development was to tackle underserved but potentially profitable market segments, such as private banking, or to find other untapped and potentially lucrative market niches (which, for example, does not apply to efforts for inclusion of the unbanked poor, a segment that is ridiculously underserved in overbanked Lebanon but not intrinsically lucrative).

During the past year, big headlines about international expansions or takeovers of foreign banks by Lebanese lenders were scarce—with the one notable exception of an acquisition spree by Societe Generale de Banque au Liban (SGBL) and its chairman, Antoun Sehnaoui. SGBL made news over the acquisition of two entities from one banking group in Europe in December, and Sehnaoui was reported to have acquired a small bank in Colorado, United States, in mid-year. Overall, however, most news from local banks shown on the website of the Association of Banks in Lebanon in 2017 or reported in Lebanese media focused on corporate social responsibility, and querying top bankers about development strategies at the end the year felt like pulling teeth.

Understandable hesitancies

Put into national and global contexts going into 2018, however, any banker’s hesitancy in declaring new development opportunities is as unsurprising as reluctance in the face of painful dental procedures. Foggy perspectives, first of all, afflict the Lebanese economic and financial environment, due to the local political climate. That point has been demonstrated indisputably in November of 2017 to all who even might have dared to dream differently.

Foggy perspectives intrude equally, however, from the global economic-policy environment. The impairments of vision in this regard relate to long-standing debates over banking rules and policy twists in the United States, among other things. This is not just about Hezbollah-bashing legislation from American lawmakers but also about legislative measures with global economic implications. At the end of 2017, there is no apparent certainty about the future regulatory climate in US banking, although this climate is widely assumed to become friendlier for financial corporations. In spite of this policy expectation, there certainly are some mixed international impressions of movements on the US regulation and deregulation front—buzzword Dodd-Frank—which are certain to influence banking internationally.

A December announcement about a reform agreement on the Basel III rules by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) also tended to leave its own space for ambiguities. The final reform framework for the 2010-initiated Basel III package aims, as BIS states, “to restore credibility in the calculation of risk-weighted assets.” Titillations linked to this reform will quite likely be limited to central bankers and experts in advanced financial accounting, but one noteworthy facet of the package is that it gives countries and banking institutions extended deadlines before the announced reforms come into effect in 2022 and have to be fully implemented in ten years.

More relieving for concerned central banks and government treasuries than the timeframe might actually be that the reform package does not talk about risks when it comes to sovereign bonds. These will still enjoy statutory innocence on bank balance sheets and will be zero-risk assets, since the insolent idea that sovereign bonds could behave any other way was not approved by the Basel committee, which includes central bankers and government-appointed regulators from 28 jurisdictions and operates on a consensus principle.

Next, the changes in the US taxation system, which are yet to be adopted and signed into law at time of this writing, have economic and equity market implications of uncertain magnitudes and directions in the horizon for the coming few months. Some European bank economists described the corporate US tax cuts in their 2018 outlooks as pro-market and not yet priced-in in December 2017, but the prospects of these cuts also caused some vocal concerns among government economists in the major European export power, Germany.

On the political level, prospects of risk were stoked significantly at the end of 2017 by the ignominious Jerusalem decision by the US president. Such a move can only serve to remind humanity that wars in history have been triggered—if not caused—by irrational elements, from deliberate insults of national pride to football games. Especially from a vantage point in the Eastern Mediterranean, the move is a painful reminder of the recurrent misperception of man as rational being. Optimistic concepts of eternal peace as based on enlightened treaties, or as capitalist peace predicated on the global spread of a fast-food empire, have unfortunately not proven sustainable, Mr. Friedman, just like the idea that no honorable journalist of our times could ever debase himself as a sycophantic scribbler.

[pullquote]Prospects of risk were stoked significantly at the end of 2017 by the ignominious Jerusalem decision by the US president[/pullquote]

Even without a clear understanding of the regional pressure experience from bilateral Saudi-Iranian rivalries in the Middle East, which the risk quarterly of Aon, the international insurance intermediary, in late November 2017 categorized as “the major driver behind the general increase of risk in the region,” it is very hard to ignore the impression that more tinder is piling up in the world’s number-one tinderbox. Who can think about development opportunities at such a time?

Thinking about the overall uncertainty at the end of 2017, one might finally want to cast a questioning eye on market expectations for the coming year. These are generally optimistic in tenor, even if curiously worded—like one from Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BofAML), a leading wealth-advisory and asset-management player, which titled its 2018 Global Markets Research Outlook, “So bullish, it’s bearish.” But bullish indeed is the consensus of the analyst herd, and the picture is similar even from the watchdog of the developed economies, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

From the lofty vantage points of all-impressive charts, the OECD hints of raging economic bulls across member countries. In one OECD powerpoint, economic outlook projections for real GDP growth rates in 2017, 2018, and 2019 by the organization feature 39 arrows of the up, down, and flat varieties for the world, the Euro region, and individual member countries. Of the 13 arrows for 2017, 11 point up versus two year-on-year downers (UK and India). Of the arrow sets for 2018 and 2019, year-on-year development projections for 2019 have 11 down arrows, but when one compares the forecasted growth rates with the 2016 actual rates, each of the three years in the projection timeframe is overwhelmingly up.

That is to say, relative to 2016 actual, projected GDP growth rates for OECD countries are flat only three times. Seven of the 39 arrows point down. That leaves 29 upward projections across the economically dominant part of the world in this and the next two years when compared with 2016. This is scary.

On one probably heuristic level in this writer’s mind, the unscientific scare factor is that overwhelmingly bullish expectations for a coming period in the global economy are associated with years that turned out as leading down to quite the opposite of dominant expectations, like 1928 and 2006.

[pullquote]Seven of the 39 arrows point down. That leaves 29 upward projections across the economically dominant part of the world in this and the next two years when compared with 2016[/pullquote]

It is difficult to forget that in 2006, the IMF opined in the foreword of its September World Economic Outlook (WEO), “Our baseline is that world growth will continue to be strong.” This confident assertion was followed by the fascinating (and bullish) assurance in the April 2007 WEO that “continuation of strong global growth” was the most likely scenario, because risks had declined from the previous year, and compared to six months prior there was “less reason to worry about the global economy.”

What differed markedly from these opinions was not merely the April 2008 WEO acknowledgement that “the world economy has entered a new and precarious territory,” but rather the entire geo-economic experience of the years that followed.

If we pivot back to current 2018 views, Copenhagen-based international trading specialist Saxo Bank at the end of November confessed to having a contrarian view on global growth in 2018 vis-à-vis an overly rosy consensus among financial augurs. Saxo enigmatically opined in its global macro outlook that “2018 is certainly the most favorable occasion for a bubble burst since 2007.” Open warnings seem to be out of favor with analysts this year, but is an overall aversion to trouble the waters more on the good or on the bad side as far as predicating existing trends?

What works?

From an emerging-markets angle, beyond general intuitive uneasiness it might be a rational fear that things that are good for the big players in the global economy do not have to be in the best interest of countries that comprise the precariat of the global sphere in terms of their absolute shares in world GDP. Usually, these countries do not even appear on index radar screens as frontier economies. This differential between analytics of the global and local could mean that consultation of crystal balls and tarot cards are superior to arduously googled research papers and outlooks by leading international-bank economists. Or, at least, it could mean that inquiries of what worked in 2017 for the top Lebanese banks are preferable to the assessments by their foreign peers who do not have Lebanon in the center of their analysts’ radar, or anywhere else on their research screens.

So what did work for the Lebanese alpha banks with deposits in excess of $2 billion in 2017, and thus might also help them to rich harvests in 2018?

BLOM Group, Lebanon’s runner-up in banking power and winner of 20 different accolades in various financial award categories in 2016 and 2017, according to its website, said in a November 2017 blog entry by its Blominvest unit that over the first nine months of 2017, BLOM Bank “attained the highest level of operational, non-exceptional net profit” and also topped the ranks of the four listed Lebanese banks in two crucial return ratios.

“BLOM Bank recorded the highest [return on average common equity] at 16.93 percent and the highest [return on average assets] at 1.55 percent,” the entry read, before adding that the percentage growth of assets and the lending portfolio at BLOM—with asset growth of 7.7 percent and loan growth of 6.4 percent in the first three quarters of 2017—was higher than that of its listed peers, AUDI, Byblos, and Bank of Beirut.

Asked what was behind the bank’s success leadership in 2017, Saad Azhari, BLOM Group chairman and general manager, explains that the bank’s growth in assets and deposits as well as its higher loan growth than the sector was “definitely linked to the acquisition of the HSBC loan portfolio, which added about $500 million.”

While the acquisition of HSBC Middle East, which BLOM officially announced in November 2016 and completed in June of 2017, did not greatly boost BLOM in size, it was very beneficial for the group’s trade-banking activities, where it facilitated a strong increase in commission income from letters of credit (LC) and letters of guarantee (LG). According to Azhari, the acquired HSBC Middle East business adds some 2 to 3 percent to BLOM’s business, “but in terms of commissions on LCs and LGs, the increase is about 50 percent of the consolidated BLOM activity in this area, and when taken for Lebanon alone, the volume of LG [and] LC was doubled,” he says.

Some processes and digitization at BLOM could also be improved through integration of HSBC staff, and BLOM also succeeded in retaining a very high share of the acquired customer base. “The add-on to profitability is also good; while the size of HSBC portfolio is small, it will add to profitability in future,” Azhari acknowledges, adding that the acquisition worked “overall better than expected.”

[pullquote]2017 was a year of subdued appetite for growth among all Lebanese banks[/pullquote]

When asked about the best development prospects of Lebanese banking going forward, Azhari pointed to the inopportune timing of such considerations in the politically charged month of November 2017, and expressed hope that the problem would be temporary. As positive general perspectives, he cites the oil and gas sector, as well as bank investments into tech entrepreneurship under Circular 331, from Banque du Liban (BDL), Lebanon’s central bank. Granting oil and gas licenses “will definitely open new doors, as there will be companies that will be suppliers and services providers. This activity will boost investments, so I think the oil and gas sector will be an important sector for the future,” he says.

In the view of Freddie Baz, vice-chairman and chief strategist of Lebanon’s largest financial entity, Bank Audi Group, 2017 was a year of subdued appetite for growth among all Lebanese banks. He points to challenges in the two main countries with a Lebanese banking presence abroad, Turkey and Egypt, to explain why pursuit of growth in the external markets was less vigorous than in some previous years. “Both countries are facing many challenges. These challenges are of [a] short-term nature, but short-term strategies [for foreign operations of Lebanese banks] are much more in a consolidation mood than in growth mode,” he explains, adding, “At the same time, in Lebanon, we are seeing a lot of volatility and many unknown parameters. They do not exist to the extent of generating big fears and concerns, but people want to see improvements. These are again being delayed; the situation is delaying, delaying, delaying.”

Underestimated

Emphasizing that Lebanon’s performance over the past 25 years is likely to be underestimated in comparison to other Arab countries, Baz points out, “For reasons of Lebanon’s sectarian dimensions, sensitivity toward regional conflicts is probably the highest among peers in the region. But amazingly, when you look at the long run, there are interesting numbers concerning growth.” He cites recent studies conducted by Bank Audi’s economic research team under Group Chief Economist Marwan Barakat, which show that average annual GDP growth in Lebanon is in the 4 percent range in the past 27 years and, compared to the region, only 20 or 30 basis points lower when viewed over long periods (from 2000 to 2017 in the first comparison, and from 1990 to 2017 in the second comparison).

What impacts the perception of Lebanon are long-standing but largely consistent risks and the presence of high volatility. “The bottom-line reading is that Lebanon gets affected by regional conflicts and domestic difficulties much more than the region, but its capacity to rebound is also much faster. The volatility is high, but in the very long run, Lebanon always catches up,” Baz says.

The perception of Lebanon as especially risky or slow in economic development and political economy might explain many unfavorable perceptions of the nation and its financial industries among the country’s residents and foreign observers, including perceptions of measures relating to the overconcentration of the monetary side in the national mix of fiscal and monetary policies. In 2016, the best things that happened to the banking sector arguably were the central bank’s unconventional measures, driven by BDL’s desire to fill up its vault with foreign-currency reserves, which was explained by the central bank as a measure in the national interest.

It is undisputed that this unusual financial engineering translated for commercial banks into a year that was described with epithets from atypical to significant, but it was not so much by their own initiative as by their willing and skillful participation in the central bank’s scheme.

One of the possible macroeconomic advantages that the World Bank’s Fall 2016 Lebanon Economic Monitor envisioned as result from the 2016 financial engineering was “a positive impact on private lending and, thus, economic growth” from the rise in Lebanese lira liquidity at the commercial banks, contingent on “sufficient demand for the additional liquidity in local currency.” (This was the only advantage noted by World Bank economists with respect to the macro economy, versus four disadvantages.)

In September 2017, Bankdata, the analyst firm and banking consultancy, noted, “It is worth recalling that Lebanese banks are increasingly benefitting from the stimulus packages of the Central Bank of Lebanon providing interest incentives for [Lebanese lira] lending over and above an increasing liquidity in LL which is being more and more targeted toward lending at competitive rates.”

Analyzing alpha bank lending trends over nearly seven years, from December 2010 to September 2017, Bankdata told Executive that annual lending growth in the period was highest in 2013, with $7.3 billion in additional loans, while observing that “the pace has slowed substantially since December 2015, with additional loans of $2.6 billion over the past 21 months.” According to the analysis from November 2017, alpha banks’ overall loan portfolio “stood at $35.8 billion at year-end 2010, and reached $66.5 billion in September 2017, an incremental $30.7 billion, of which 70 percent or $21.4 billion [was denominated] in foreign currencies and $9.3 billion in local currency.”

The share of local-currency loans in the total rose steadily from around 15 percent at the beginning of the period to 22 percent at its end, the consultancy said. By type of loans issued over the past three years, corporate loans represented 40 percent of the overall portfolio, according to Bankdata, and reached almost 50 percent when counting commercial real estate loans. Small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) and housing loans each accounted for around 15 percent, and retail loans for 12 percent of the total.

Not the time

As the two top bankers, Azhari and Baz, both emphasized, the purpose of the financial engineering of 2016 was to improve dollar reserves at the central bank and simultaneously increase the equities of banks. “Considering the high cost of attracting dollars, the purpose of the financial engineering was not to increase lending,” Azhari says.

Baz notes that banks amassed large amounts of liquidity through the financial engineering, which they absorbed, and that any offer to lend lira at good rates was the result, but not the target, of the engineering. “The result of the engineering was increased liquidity, and banks had to use this liquidity. This is notwithstanding the notion that we need at a certain point to de-dollarize our economy, but this de-dollarization cannot start before fundamental imbalances are adjusted,” he says, referring to Lebanon’s deteriorating capital stock and dependency on inflows, which he characterized as a form of the resource curse.

Pointing to high correlation between GDP growth and loan growth in the country, he refers to the sluggish economy as related to the equally weak loan growth in 2017. “In Lebanon, additional lending in the economy is commensurate with 1.5 to 2 percent real GDP growth. If you want to achieve 5, 6, 7 percent, you need to double the amount of lending,” he notes. When one puts all this into context of economic pressures experienced by Lebanon from 2011 till today, one sees the role of the BDL measures as positive, when Governor Riad Salameh was faced in 2016 with a weakening balance-of-payment position at a time when money inflows could be mobilized. “One needs to take money when it is available, because when one needs it, one may not find it,” Baz says, adding that in his view, debates over the cost of the measure were missing the point of comparing the cost of such an adjustment with the cost of a social crisis that could result from not undertaking it.

Looking into virtual opportunities

The sum of volatile economic realities in Lebanon, global uncertainties, and ever-more-complicated regulatory and operational environments for the banking industry in the country might leave the 21st century’s digital frontiers as only the palpable frontier of banking opportunities. Frontiers are always good for adventures and opportunities. They lead to unknown and perhaps even virgin territories, although the natives might object to the viewpoint. But there are no natives on the other side of the digital frontier (one assumes) and that makes it doubly attractive to venture into digital exploration.

The drawback is that the digital realm is not so new and untouched as it was 20 years ago, when the first wave of new finance settlers ventured there during the first bubble phase of the internet revolution—and soon beat retreats after the burst of the dot.com bubble, at least from the concept of “online-only” banking. More than 15 years after the burst, the internet is a standard banking channel and IT investments, online services, and cybersecurity for banks present themselves as must-have development obligations. Just as a bank operating during the Industrial Revolution needed to invest in a building, a counter, and a vault, banks in the current age need to have online services, advanced IT, and powerful cybersecurity. Lebanese banks have allocated investments to their IT departments, from upgrading core systems to adding new processes, they flaunt their online services and are aware of the cybersecurity issue (although it has to be noted that the legal and technical cybersecurity framework in Lebanon is still in considerable need of development on national level).

[pullquote]Banks in the current age need to have online services, advanced IT, and powerful cybersecurity[/pullquote]

The frontier adventures of 2018 and the next few years might be hidden in the jungle of cryptocurrencies, as the bitcoin-mania at the end of 2017 underscores. However, the path into this territory does not yet appear all that clear. Salameh, who in the past few years had been criticized by financial-tech entrepreneurs for blocking the concept of cryptocurrency adoption in Lebanon, recently readjusted his outlook and started talking about a sovereign digital currency, for example, at a cybercrime prevention conference in November. However, it seems that the Lebanese banking sector still has to tune its sensors to the cryptocurrency and distributed ledger technology, not at only in development practice but even in concept. BLOM Chairman Azhari enthused to Executive that the bank already has its version. “We ourselves, if we can say so, have a virtual currency, our golden points. It was started before [the topics of Bitcoin and Blockchain came into existence] and our customers used their golden points to buy merchandise all over the world.”

Loyalty points, in technical terms, are known as tokens. Under a well-established concept they are used by many consumer focused companies, including retailers, airlines, and banks, and they have a specific purpose: to reward and enhance customer loyalty, duh. Importantly, the issuers control their generation, distribution, value, and shelf life. This limits their qualities as fungible, transferrable, or tradeable digital means. Cryptocurrencies and their safety features (the blockchain) are generally designed to be tradeable, have unlimited lifespans, and are thought of as fungible.

The concept of a digital sovereign currency in Lebanon under BDL supervision comes with many questions. Moreover, the timeframe for any adoption of such a scheme is yet to be determined—and if the time that has passed since the first reference to an ETP in a public speech by Salameh is any reference, nobody needs to trouble their mind over a sovereign or any other cryptocurrency in Lebanon for a few years yet. For Audi’s Baz, the much hotter agenda item for Lebanon is the creation of the electronic trading platform (ETP) attached to the Beirut Stock Exchange. “Digital currency talks are very premature for Lebanon. In my opinion, the ETP is more important, and the [BDL] governor is keen on developing it,” he enthuses, adding that not mere words but real action has been dedicated to the establishment of an ETP in the Lebanese context, and needs to result in more concrete steps.

A good starting point for reviewing the Lebanese banking sector at the end of 2017 to study a document that was published early in the year and is referred to in financial High Valyrian as a FSAP. For common folks, this stands for Financial Sector Assessment Program. A FSAP is undertaken by the institutions missing from Westeros: the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. To augment insights from the FSAP on Lebanon, which was published under the title Financial System Stability Assessment, one can turn to the findings of the IMF’s Article IV consultations on Lebanon.

For readers who are interested in super-condensed material, the entire economic narrative of Lebanon in 2017, and 2016 before it, is contained in FSAP’s opening paragraphs, in just two sentences: “Lebanon has maintained financial stability for the last quarter-century during repeated shocks and challenges,” but “over time, macroeconomic and financial vulnerabilities have accumulated.” This is the Lebanese paradox of endurance, resilience, and risk in a nutshell. In a sense, nothing more needs to be said about the matter of the tiny Lebanese economy.

As for the banking sector, the FSAP elaborates that despite economic and political shocks, “confidence in the banking sector has been sustained … and the banks have grown and remained profitable.” About Banque du Liban (BDL), Lebanon’s central bank, the report observes, “BDL plays a critical role in sustaining confidence, although, without sustained fiscal adjustment, there are limits to these policies.”

The assessment, which runs to nearly 80 pages in body text and appendices, concludes by saying: “Developing a strategy that addresses the elements noted above, including eventual withdrawal of BDL’s economic stimulus programs, and bringing in views from the financial industry and other stakeholders, could build consensus around reform priorities and sequencing with due regard to financial stability and integrity concerns.”

[pullquote]There are 52 insurance companies for a $1.5 billion market. This results in fierce competition and lower market standards[/pullquote]

This is just as true at the end of 2017 as it was a year earlier. What the paper was naturally unable to predict, however, was the journey of national sentiments from the end of last year to December 2017, a whitewater adventure in a raging stream of unpredictable political twists and economic turns. On this ride, the banking sector proved to be an essential raft of stability, providing stabilizing effects on the financial economy, such as wealth management and insurance, and on the entire country. Moreover, while the past year saw some rumors and debates over allegedly impending financial and economic doom owing to the central bank’s monetary policy, the year’s dangerous instability was not at all related to banking or BDL monetary policy. It arose from pure politics.

The 2017 narrative in brief

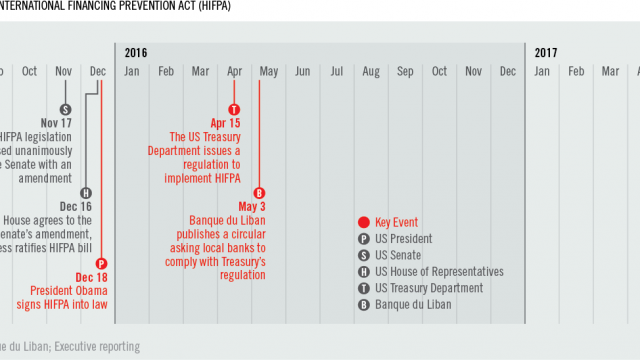

In rough strokes, the Lebanese ride through the year was defined by local politics and international circumstances. The journey of notable twists began with political declarations of optimism after the formation of a government in December 2016. Based on this optimism, banks and economic stakeholders started January 2017 full of hope for improved performances. For bankers, February brought with it the first turn toward concern, over speculations about the upcoming end of BDL Governor Riad Salameh’s term. Then, later in spring, concerns in the banking sector grew as reports of new American anti-Hezbollah measures emerged. Speculations and rumors over Salameh’s resignation and debates in the United States over the Hezbollah International Financing Prevention Act (HIFPA) built up uncertainty throughout spring 2017, accompanied by some research essays and speculation about Lebanon’s long-standing economic imbalances, the stability of the lira, and sector-internal matters such as upcoming board elections at the Association of Banks in Lebanon. While political unity and reform remained an issue throughout the first half of 2017, May and June brought the Salameh question and Lebanese political concerns back to the front burner, via the urgently needed new election law.

From outside Lebanon, the global implications of the new regime in the United States and fears over a possible spread of populist influences in Europe spiced up the local journey with imported political concerns, until election outcomes in the Netherlands and France calmed minds all around. In the context of global developments, however, tensions soon erupted into a new bout of mad politics, with North Korea on top of the insanity pole. A competing political performance on center stage was delivered by new global twittertainer, The Donald, with his bizarre “Trump First” show.

Leading financial markets in the US and Germany, in the meantime, achieved stronger growth than pundits had predicted at the onset of 2017. Throughout the year, large economies reported improvements; the picture was peppered in the year’s second half with the occasional dire warning against complacency and “frothy valuations,” uttered by financial powers like IMF head Christine Lagarde or the Bank for International Settlements in Basel.

In Lebanon, July brought a boost of relief to banking emotions as Salameh’s new term was confirmed. Lebanese banking and political officials polished doorknobs in the US in August, while the Lebanese focused on their summer vacations. HIFPA worries, meanwhile, were swept under a rug of artificial calm for a while, only to reappear later in the year (see below for the timeline of HIFPA adoption in the US). In mid-summer, the mood was again dampened by another wave of rumors about trouble for the Lebanese lira and the economy, peaking in a paper in which noted economist Toufic Gaspard argued his case for addressing the “Financial Crisis in Lebanon.” The paper even triggered a sanctimonious response from the usually taciturn BDL.

October came with more optimistic declarations, as locally-held international and national conferences kept bankers on their feet. But any hopeful mood was blown come the first weekend in November and the surprise resignation that Prime Minister Saad Hariri chose to deliver via a Saudi-owned TV network from Riyadh. Thus ensued a month-long story of verbal panic, damage control, and reassurances, followed by ostentatious relief in early December.

Throughout 2017, BDL Governor Salameh iterated his assurance of stability in conferences, interviews, and interventions on all sorts of occasions. At practically every major appearance, he repeated the statements which he had given at the end of 2016, such as, “Our holdings in foreign currency allow us to think that we can keep the Lebanese lira stable,” or affirmations of determination for maintaining interest rates. At a conference in July, just to cite one example, he offered his mantra, “The Lebanese lira is stable and will remain so,” and assured his audience, “Interest rates in Lebanon are stable.”

In no month of 2017 could one count more of these assurances than in November, when the governor voiced his assurances of stability not only nationally, but also sought to appease international concerns about the Lebanese situation. Even when asked in mid-November by a CNBC interviewer how frustrated he was about the disruption of Lebanon’s economic recovery by the latest political turn, Salameh’s answer was, “The Lebanese lira will remain stable.”

By early December 2017, the assurances appeared to have achieved their purpose. Although political question marks still linger en masse and no conclusive summary on the performance of Lebanese economic indicators for full-year 2017 can be drawn up, the performance of the banking sector for the first nine months of the year has been—when compared also to the rather exceptional boon year of 2016—reassuringly stable. Banks in the top tier of the sector delivered remarkable numerical normalcy. Assets rose, deposits rose, and even lending showed increases that seemed commensurate with the overall economy’s (subdued) growth (see comment by Bankdata).

Details about the loan activities by the largest Lebanese lender, Bank Audi, reinforce the impression of shifts in accents within overall persistency. Grace Eid, head of retail banking at Bank Audi Lebanon, informs Executive that the lender saw “strong development in domestic-loan issuance in Lebanese lira,” especially with regard to personal loans. Eid notes an inversion in this segment in particular, saying that in 2017, sales of lira-denominated loans outperformed dollar-denominated ones, whereas in the year 2016, “45 percent of our personal loan executions were in Lebanese lira, versus 55 percent in US dollar.

“Regarding the home loan, no major changes were witnessed during the past two years, as 80 percent of our lending portfolio remained in Lebanese lira. Although our strategy in 2017 was to increase car-loan sales in Lebanese lira, as we have introduced a new plan in this currency, 99 percent of our lending portfolio was in US dollars,” she elaborates.

In another area where bankers increasingly started seeking to better serve the Lebanese market, small and medium enterprise clients picked up on the idea that large banks could help them with their specific needs, Bank Audi confirms. “[Besides a] remarkable increase in the sales of the retail banks’ core retail products, starting with the personal loan and followed by the home and car loans, we have witnessed, in the SME banking sector, a high demand [for] products that finance the working capital (operating expenses), followed by [demand for] subsidized loans from the central bank for long-term financing,” explain Eid and Hassan Sabbah, head of SME banking at Bank Audi.

Words from stakeholders in other parts of the financial economy

In addition to commercial banking, with its ever-more diversified retail, small commercial, and corporate offerings, other sectors of the financial economy showed either concrete development or at least promise of future development. From the banking sector’s chambers of wonders—the wealth management and private banking space—come tidings that Lebanese High Net-Worth and Ultra High Net-Worth Individuals (HNWI and UHNWI) found themselves able to lean back comfortably on rich cushions. Leading private bankers in Lebanon who opened their hearts to Executive in fall 2017 assured that wealth deities are exceedingly kind to their clienteles. Wealth management specialists representing Swiss private banking group Julius Baer likewise signaled that their local clients have nothing to fear.

During a visit to Lebanon in early November, Remy Bersier, head of Emerging Markets at Julius Baer, confirmed that the bank, which has had an office in Lebanon since it acquired the Beirut operations of Merrill Lynch, has not seen any unusual behavior or irrational capital-flight impulses from clients here. “We are committed to growing here, and are recruiting. We want to reach a higher level of access to the UHNWI segment,” he says. With a strategic concentration on the three pillars of sustainable profitability, client experience, and reputation, “We have many projects ongoing today in the bank and are really careful to respect regulations. One of the key topics is to bring the bank into the next decade and, hopefully, century. Reputation is not negotiable,” he emphasizes.

Capital markets in 2017 still were as they had been in previous years: underdeveloped to the point of invisibility. But as the FSAP assures and local capital-market wizards confirm, Lebanon’s regulatory Capital Markets Authority (CMA) has not been idle. The FSAP reports said that “Over the past five years, the CMA has built capacity and is now well established as an independent regulatory authority,” and acknowledged that the institution, which is also chaired by BDL Governor Salameh, “has prepared regulations in line with international best practices covering licensing and registration, market conduct, business conduct, securities offerings, listing rules, and collective investment schemes, and has put in place a supervisory program.”

The CMA’s key message to the market in 2017 was confidence, CMA Communications Head Tarek Zebian conveys to Executive. “Today, investors and financial institutions strongly feel the presence of CMA while conducting securities-related business activities. In 2017, CMA formulated, in coordination with experts from the World Bank, a ‘blueprint for market development,’ a document that was shared and consulted upon with all stakeholders of the CMA, including the office of the prime minister, representatives of public institutions, and financial industry professionals. This signaled to the various participants our long-term commitment to shift the capital markets to the forefront of financial activity in Lebanon,” Zebian says, adding that the authority’s measures should ultimately translate into vibrant capital markets which enhance economic growth.

Pointing to progress in the drawn-out saga of attempting to transform the Beirut Stock Exchange (BSE) into a high-performing entity and the vibrant center of Lebanon’s capital markets, Zebian affirms that a cabinet decree issued in August of this year initiated the process of establishing a new entity under the name Beirut Stock Exchange sal, transferring all assets of the “dismantled government-owned Beirut Stock Exchange to the new sal company.” According to him, the new BSE is to be sold within one year.

Among a host of other new measures, in 2017, the CMA signed a memorandum of understanding with Lebanon’s Insurance Control Commission (ICC) at the Ministry of Economy and Trade. “In essence, the MoU clarifies the relationship between both authorities, especially toward investment insurance policies that has dual oversight as a result of securities-linked (unit-linked) products underlining their formation,” Zebian explains. It is expected that CMA and ICC will exercise joint jurisdictional oversight and collaboration in the interests of insurance policyholders and investors in this industry.

The insurers’ lot

The Lebanese insurance sector is engulfed to quite some deGree in a dichotomy that is not all that dissimilar to the contradictory state of the country’s economy. All insurance companies are private sector players. The companies pride themselves in being pioneers of practicing insurance skills in the region. However, no single insurance company has been listed on the BSE, and sector assets historically represent under 10 percent of GDP. Banks regularly outdo insurers in terms of sector-asset growth and, as the FSAP notes, insurance assets stand small when compared with the banking industry.

In the FSAP description, “The ICC is instrumental in maintaining the industry in a generally sound condition,” but “the insurance sector faces structural challenges to its sound development.”

AXA Middle East confirmed that 2017 saw an increase in competitive pressures in the local market, resulting in decreases in premiums. Coupled with cost increases from the expected VAT increase and rising costs for medical care, the company foresees a “reduction of profit or even losses for insurance companies.” According to Reine Kattar, AXA Middle East’s brand, communication, and reputation manager, the company, which is affiliated with the multinational AXA Group, is also witnessing some cost pressures from an increase in regulatory action, a relatively new phenomenon in the Lebanese insurance market. “Governance requirements are increasing, which leads to higher cost in compliance, risk management, and internal audit,” she explains.

New regulatory pressures included, AXA Middle East General Manager Elie Nasnas confirms growth prospects for the insurance industry. “I can see a growth in the insurance sector for the coming years. This can only be offset currently by the lack of tax incentives for life products,” he tells Executive, adding that the incentives for life insurance savings products exist in many countries and motivate owners of small as well as large businesses to buy these insurance programs.

“Also needed today is a unanimous decision by the Ministry of Finance to exclude the costs of taxes related to health and savings insurance policies from the general tax on wages and salaries, which will in turn encourage business owners to invest in such policies. A driving factor which will drastically help the insurance sector would be a policy shift of making some currently optional policies to become mandatory insurance covers. Most notably, these are civil liability for material damages as well as insurances against fire and natural disasters. In the past, these types of policies were seen as optional, but in today’s world they are indispensable to our everyday lives,” he says.